|

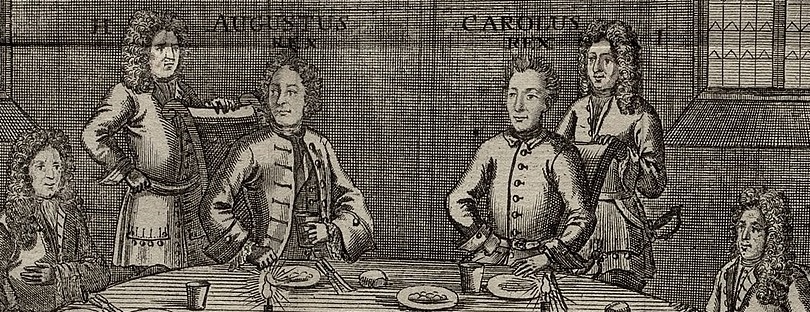

Left: A portrait of the meeting in Potsdam 1709 with Augustus the Strong

of Saxony, Frederick I of Prussia and Frederick IV of Denmark-Norway. Right:

A posthumous portrait of Peter the Great of Russia.

The anti-Swedish coalition got a disastrous start in 1700

with each member failing to achieve their objective and one of them

defecting from the war, a second suffered a crushing defeat and the third

member expressing a desire to negotiate for peace. It certainly appeared to

outsiders that the war would be a short one and thus the great powers

offered both mediation and propositions to recruit the belligerent countries

as allies in the coming War of the Spanish Succession. However, despite the

rocky start the coalition would remain in place with two members actively

fighting the war and the third one promising to re-join the war at an

appropriate time. Even the treaty of Altranstädt in 1706, which left Russia

alone in the war, did not permanently end the coalition since both Denmark

and Saxony began negotiations to re-enter the war after the Swedish army

left Saxony in 1707. In 1709 the anti-Swedish coalition of 1699 was fully

restored and this time it was more lasting.

Denmark

Denmark had been forced out of the war after the Maritime

powers helped the Swedes to land an army in the poorly defended Sealand and

thus threatened Copenhagen. The treaties which the Danes had signed with

Saxony and Russia had forbidden any member to sign peace with Sweden

separately, but the Danes claimed that they had not violated those terms.

The peace at Traventhal was technically only between Denmark and

Holstein-Gottorp since Denmark and Sweden had technically not been at war.

The Swedes together with the Maritime powers had only acted as guarantors of

the Altona treaty from 1689 and were not officially considered as

belligerent parties of the conflict. The Danes thus reassured their allies

that the Traventhal peace was in no way a defection from the coalition and

that they would soon start a proper war against Sweden.

Actually the Danes first planned to attack the Swedes

already in August 1700 by sending out the Danish navy against the weaker

Swedish naval squadron outside Sealand and thus isolate the Swedish army

still on Danish soil. The Maritime powers thwarted this plan however by

prolonging the presence of their navy in order to protect the Swedish

evacuation.

Later in the year the outcome of the battle of Narva gave

the Danes cold feet and they became unsure whether their allies were

committed to remain in the war. So they chose to wait and see before they

decided to enter the war. The battles of Düna and Kliszow had the same

effect and once the Swedish army was firmly established in Poland the Danes

became very afraid of starting a new war without Prussia as an additional

ally. The Danes were haunted by the memories of 1643-45 and 1657-58. So

long the Swedish army was within striking distance from Denmark’s southern

border, the Danes had good reason to believe that Charles XII would give a

Danish war top priority and drop everything else. Therefore they desperately

wanted Prussia to join the war and act as a shield against the Swedish main

army. Failing that they just had to wait until the Swedish army marched back

to the east again.

Russia

There was an agreement between the allies that Peter I

would not join the war until he had ended his conflict with the Ottoman

Empire. But with the intervention of the Maritime powers the Danes began to

desperately plead to the Russians to hurry up and attack Sweden or otherwise

Denmark would be forced to abandon the war. Alarmed of this Peter I decided

to rush through the peace negotiations and settle for less than desired

terms. But when he then invaded Sweden, Peter I became infuriated when he

learned that the Danes had signed the peace of Traventhal. The Saxons did

not behave much better when they shortly after the Russian invasion decided

to end this year’s campaign season. That made it an easy decision for the

Swedes to concentrate their forces against the Russians who were inflicted a

devastating defeat at Narva. Peter I blamed his allies for this and he made

his great anger known to the Danish envoy in December 1700 who felt the

atmosphere at the unpolished Russian court so hostile that he feared for his

personal safety. The Dane could however report back to Copenhagen that there

were no signs of defeatism during his meeting with the tsar. Peter I’s mind

was fully preoccupied with the next campaign season and his desire to exact

revenge for the battle of Narva.

But to continue the war Russia still needed allies and

his last one appeared to have second thoughts. That put Russia at a

disadvantage when Peter I and Augustus met at Birsen in February 1701 to

renew their alliance. Augustus managed to secure favourable terms such as a

Russian auxiliary corps of 15 to 20 000 men, a subsidy of 200 000 reichsthaler to be paid every year for two years and the promise that he

would get Livonia and Estonia if the war was successful. This effectively

made Russia the junior partner of the coalition since the absence of the

auxiliaries sent to Saxony meant that Russia would not be able to carry out

any large scale offensive of their own.

Nevertheless, the campaign season of 1701 did not go much

better than the preceding year. The Saxons were defeated at Düna and they

blamed this on the Russian auxiliary corps which had refused to assist them

in the battle. The Russians on the other hand felt that they had yet again

been betrayed by the Saxons when they abandoned Courland and left the

Russian corps alone with the Swedes.

As the war dragged on more treaties would be signed

between Saxony and Russia with similar results, both parties accusing the

other for not honouring their commitments. The once so good relationship

between Augustus and Peter I deteriorated and was substituted with

animosity. The idea of signing a separate peace with Sweden thus became very

tempting for Peter I. His demands were however completely unacceptable for

Sweden.

Peter I conquered the mouth of the Neva River in 1702 and

quickly began construction of his great dream, the port city of Saint

Petersburg. Making Russia into a naval power was an obsession of his and he

would never settle for anything less than keeping the area around the Neva

River and the island of present day Kronstadt, no matter how badly the war

went. Preferably he wanted all of Ingria and Carelia as well, but during the

darker moments of the war he was willing to settle for the smaller territory

and even compensate Sweden by ceding Russian territory in return for that

area. Although, after the great rebellions against his rule in 1705 he no

longer dared to cede any Russian land and instead proposed Polish territory

as compensation.

Sweden could however not allow Russia to gain access to

the Baltic Sea and build a navy since that would fatally undermine the

Swedish realm. Sweden had long coasts and scattered provinces which made

naval control of the Baltic Sea absolutely essential for the survival of

their empire. But since the Danish and Swedish navies were evenly matched a

newly created Russian navy would put the Swedes at a serious disadvantage.

The Swedish demands were instead that Russia returned all

occupied territories and offered compensation for the damage it had done to

Sweden. The compensation should preferably be in the form of Russian

territory but Charles XII appeared to be open to other alternatives when

Prussia offered to mediate in 1705. This mediation would however go nowhere

since Peter I was completely unwilling to give up his beloved Saint

Petersburg. The next year after the battle of Fraustadt the Prussians tried

again, this time desperately trying to convince Peter I to be reasonable

since they feared a continued war would result in total Swedish domination

of North-eastern Europe. But to no avail, Peter I was determined to keep his

Baltic port. In 1707-08, through English channels, he proposed a peace with

Sweden on the terms that he was to keep the area around Saint Petersburg

permanently and also Narva for some years. At the time these were totally

unreasonable terms and Sweden and Russia had to settle their differences on

the battle field.

Saxony

The weak link of the coalition was the untrustworthy

Augustus. He was the ultimate opportunist who would stop at nothing to

further his great ambitions. He had no loyalty to anyone but himself and

deceived friends and foes alike. This behaviour may have given him short

term advantages but it hurt him in the long term since his character flaws

soon became widely known. This resulted in Charles XII refusing to engage in

negotiations with him on the count that any treaty signed by him was not

worth the paper it was written on. Likewise, potential allies such as

Denmark and Prussia hesitated to join the war because they feared Augustus

might just use that to make a quick peace with Charles XII and possibly even

switch side.

Augustus’ diplomacy was very active and often

contradictory throughout the war, thus making it difficult to record all of

it here. But it is worthwhile to note that his ambitions were not limited to

seizing territory from Sweden. Even though he had become king of Poland as

the anti-French candidate he soon began attempts to smooth his relations

with France and forge an alliance with them against Austria. The prospect of

a war over the Spanish succession was viewed by him as a great opportunity

to conquer Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia among other territories and then

replace the Habsburgs as Holy Roman Emperor. These negotiations occurred at

the same time as he was preparing for war against Sweden and not even his

own diplomats knew that he pursued two different strategies at the same

time. The Danish diplomats suspected it though, but Augustus denied it to

them. And when the news about the Saxon invasion in Livonia broke, Augustus

had the audacity to ask for military support from France and the other great

powers by claiming that it was the Swedes who had invaded his kingdom and

not the other way around, as well as reassuring the French of his continued

interest in an alliance against Austria.

After Denmark was forced out of the war Augustus found

his home country dangerously exposed since the Saxon army was engaged far

away in Livonia. The prospect of an imminent Swedish invasion of a

defenceless Saxony made him declare an interest in peace negotiations and

France offered to mediate. Charles XII had however by now acquired an

intense contempt of Augustus moral character and regarded it as a stalling

tactic. He was not willing to engage in any meaningless peace negotiations

with him even if it meant a risk that Sweden would be regarded as the

obstacle to peace by the great powers. The Swedish military commander in

Germany refused however to carry out an invasion of Saxony citing a lack of

preparations and unclear instructions. The Russian invasion and the arrival

of a Danish auxiliary corps in Saxony during the autumn finally closed the

window of opportunity for a Swedish invasion of Saxony in 1700.

Nevertheless, the French continued their attempt to

mediate in the hope of freeing Saxony as an ally in the coming war against

Austria, although Augustus insistence on keeping the fortress of Dünamünde

which he had conquered made peace unlikely. And whatever interest he might

have had of exiting the Great Northern War and joining a War of the Spanish

Succession instead, died when Prussia and Hanover sided with Austria. As a

French ally, Saxony would have been surrounded by enemies and rather than

making great conquests Augustus would be more likely to lose territory. But

despite of this he kept on negotiating in bad faith with France just like he

had done with Sweden before the war, always promising that just some minor

modifications were needed until he would sign the treaty. He continued with

this even after the French found out that he had agreed to send an auxiliary

corps to Austria in 1702, which he of course denied straight to their faces.

The auxiliary corps he sent to Austria gave him not just money in return but

also the very valuable permit for his troops to pass through Silesia during

the war against Sweden.

The major objective for Augustus’ diplomacy in the early

years was however to convince the Polish parliament to declare war against

Sweden. That certainly looked like a strong possibility during the first

year of the war, but he was dependant on military success to seal the deal

and that evaded him. He hoped that the Swedish invasion of Polish-Lithuanian

territory in 1701 and the guerrilla attacks on Swedish troops made by his

supporters would provoke a declaration of war from either Sweden or Poland.

But Charles XII carefully avoided the traps and calmly insisted that Poland

as a neutral power had to offer him the same benefits as they had given the

Saxon troops, and thus dismissed the Polish diplomats’ one-sided demands

that the Swedish army should return to Livonia without any efforts from the

Polish side to prevent the Saxon army from operating from Polish territory.

But while Augustus was working to convince the Poles to

join him, he also repeatedly offered Polish territories to Sweden, Prussia

and Russia in exchange for peace or military support. As always with

Augustus it is difficult to determine if these offers were sincere or just

part of his attempts to manipulate people. It is likely that the offer to

Sweden was an attempt to incriminate Sweden in the eyes of the Poles. In any

event it backfired. Charles XII did not meet the Saxon diplomat but had him

arrested in early 1702 and confiscated his instructions which were then made

known to the Poles. Augustus’ attempts to woo Prussia were likewise

undermined by the Swedes who informed the Prussians about his attempts to

entice Sweden into joining Saxony in a war against Prussia. As if all that

was not enough the Swedes also intercepted a letter containing Augustus’

offer to cede Polish territory to Russia.

With a string of military defeats and loss of credibility

Augustus quickly began to lose support among Poles who now started to listen

to the constant suggestions from Sweden to depose Augustus. The turning

point was the fall of Thorn in late 1703 and the following summer a

pro-Swedish faction elected Stanislaw Leszczynsky as Polish king and then

had him crowned in 1705. But this just resulted in a Polish civil war and it

took a Swedish invasion of Saxony in 1706 to force Augustus to agree to

Charles XII’s demands and acknowledge the loss of his Polish throne.

Sweden

The

Swedish strategy when war broke out was to concentrate its resources against

Denmark. Charles XII wanted to deliver a decisive blow against Denmark and

settle the Holstein-Gottorp question once and for all. The Maritime Powers

however just wanted a quick end to the hostilities. A naval battle with

Denmark was avoided and instead of shipping the Swedish main army to Germany

it had to land on Sealand where it was completely dependent on the continued

presence of the Anglo-Dutch navy. The Maritime Powers then brokered a status

quo peace with Denmark which Holstein-Gottorp and Sweden had no choice but

to accept. With Denmark left unscathed Sweden would be in constant danger of

Danish intervention when the Swedish main army deployed in the East. The

Swedish strategy when war broke out was to concentrate its resources against

Denmark. Charles XII wanted to deliver a decisive blow against Denmark and

settle the Holstein-Gottorp question once and for all. The Maritime Powers

however just wanted a quick end to the hostilities. A naval battle with

Denmark was avoided and instead of shipping the Swedish main army to Germany

it had to land on Sealand where it was completely dependent on the continued

presence of the Anglo-Dutch navy. The Maritime Powers then brokered a status

quo peace with Denmark which Holstein-Gottorp and Sweden had no choice but

to accept. With Denmark left unscathed Sweden would be in constant danger of

Danish intervention when the Swedish main army deployed in the East.

The Maritime Powers’ alliance with Sweden would still act

as deterrence though and they did put strong diplomatic pressure on the

Danes (and the Prussians) to keep them out of the Great Northern War. But it

was clear that they only supported Sweden when it was in their self-interest

to do so. Denmark and Prussia provided valuable troops to the allied armies

in the War of the Spanish Succession so the Maritime Powers did not want

these diverted to a war against Sweden. But the treaty they had signed with

Sweden in January 1700 stipulated that they would provide auxiliary troops

in case Sweden was attacked, something they did not deliver despite of

repeated demands from Charles XII to do so. Sweden only got a partial

economic compensation for this non-compliance of the treaty.

Since the Saxon invasion of Livonia was a violation of

the treaty of Oliva from 1660 which was guaranteed by France and Austria,

Sweden asked for military support from these countries as well but would get

nothing from them too. Sweden had to face a war on two fronts all by itself.

Charles XII’s most important strategic decision was to

neutralise the Saxon threat by deposing Augustus as king of Poland. This was

also his most controversial decision since his advisors thought it was a far

too ambitious objective considering Sweden’s limited resources. Both Charles

XII and his advisors agreed that it was a highly desired goal to gain Poland

as an ally in the war against Russia, and that this was in the best interest

of both Sweden and Poland. They also agreed that Augustus was an utterly

unreliable character who could not be trusted. But Charles XII’s advisers

thought it would be possible to strike a deal with Augustus to make peace

and maybe also convince him to switch side. Charles XII however dismissed

those suggestions as too dangerous. Sweden should not be made dependent on

the goodwill of Augustus since he would not hesitate to stab Sweden in the

back if that would benefit him. Before a large-scale invasion against Russia

could commence, Augustus had to be rendered harmless. And with a new king on

the Polish throne the road would be paved for the “natural alliance” between

Sweden and Poland.

The idea of deposing Augustus most likely matured in

Charles XII’s mind during the winter of 1700-01 and was first expressed by

him in the spring of 1701. But preparations for a campaign against the

Russian fortress in Pskov were still in progress after the battle of Düna

and it was not until the autumn of 1701 that the Swedish army started to

penetrate the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth beyond Courland.

The territorial gains Sweden hoped to achieve in the war

were Courland and possibly Polish Livonia. Poland was to be compensated for

these losses by instead regaining territories previously lost to Russia in

1667. The Poles were however not so thrilled about this proposition and

comments were made that if Poland helped Sweden to reclaim territories

currently occupied by the Russians then they would owe the Swedes nothing

for Swedish help in retrieving the territories Poland lost in 1667. Since

Charles XII wanted to avoid antagonising the Poles more than he had to, he

chose to focus on the issue of deposing Augustus and left the territorial

issue to be decided after the war in Poland had been settled.

As Poland descended into civil war between pro-Stanislaw

and pro-Augustus factions it became however clear that just deposing

Augustus was not enough to neutralise him. If Sweden was to turn against

Russia, other guarantees were needed to prevent Augustus from harming the

Swedish cause. Charles XII had hoped that the great powers would give him

that guarantee, but they were unwilling to even recognise Stanislaw as king

let alone preventing Augustus from interfering in Polish affairs. Austria in

particular was very pro-Saxon and did just about as much as they dared to

help Augustus without provoking a war against Sweden. The Maritime powers on

the other hand did what they could to prevent Denmark and Prussia from

joining Sweden’s enemies, and Sweden reciprocated this by abiding with their

request to not invade Saxony while the War of the Spanish Succession

continued. The reason to this request was that a Swedish army in Saxony

would frighten the German princes so much that these would withdraw their

auxiliary corps from the fronts and thus greatly harm the allied war effort.

But when the Maritime Powers even after the battle of Fraustadt still

refused to guarantee Stanislaw’s throne, Charles XII had no choice than to

turn back west and invade Saxony.

Prussia

Another power that could have helped Sweden to keep

Augustus away from Poland was Prussia. At the beginning of the war they were

more likely to support the anti-Swedish coalition though. But this changed

when the Swedish main army adopted the north western corner of Poland as its

base of operations in 1703. With the Swedish army in close proximity of

Prussia’s core regions, an alliance with Sweden was more preferable than a

war against them. The Prussian king Frederick I was basically just an

opportunist who was willing to side with whoever gave him the best offer.

Charles XII wanted Prussia to use its considerable

influence in Poland to help him deposing Augustus. Those Poles who sat on

the fence regarded it to be of great importance to know which side Prussia

would throw its support behind. It was also Charles XII’s hope that the

Prussian army would be deployed along the Polish border to act as a shield

against Saxon incursions and thus enable the Swedish army to leave Poland

and head for Russia instead.

Prussian support was however not cheap. Frederick I

wanted Polish Prussia, Ermland and Courland, something he claimed to be a

reasonable demand since Augustus offered him the same territories if he

would join Sweden’s enemies. He quickly dropped the Courland claim though

when he learned that the Swedes wanted to keep that province for themselves.

But his demands were still impossible for the Swedes to satisfy since he

wanted territorial gains immediately if he were to support Sweden, and that

was completely incompatible with Sweden’s painstaking efforts to gain Poland

as an ally. Swedish promises that Polish territories could be ceded once

Russia was defeated and Poland could be compensated with Russian territories

had no effect on Frederick I. Even though Prussia was willing to haggle with

their territorial demands, such as reducing it to just Elbing and a narrow

coastal strip connecting Prussian Pomerania with East Prussia, they still

insisted on gaining these territories before they did anything in return. To

make matters even worse, the support Frederick I offered was limited to just

friendly neutrality and he would not even agree to recognise Stanislaw as

king before a majority of the other European powers had done the same.

What Fredrick I offered was not worth the price he was

asking for, but the talks nevertheless continued since it was a way to

prevent Prussia from joining Sweden’s enemies. Charles XII also achieved his

first objective with his Prussian strategy by signing a treaty in 1703. The

actual treaty was not really significant by itself and it was more a first

step towards a real alliance. But Charles XII made the content of the treaty

secret which led outsiders to exaggerate its importance and that influenced

public opinion in Poland.

In reality Prussia remained indecisive throughout the

Polish campaign and switched back and forth between the two camps. Prussia

regarded the Great Northern War as a once in a century opportunity to gain

territory. And even though they considered the Anti-Swedish coalition to

have a slight advantage to win the war, the two camps were regarded as so

evenly matched that Prussia would decide the outcome regardless of which

side they picked. This meant that Prussia was in the seemingly envious

position to be able to sell their support to the highest bidder. But there

were several factors that greatly complicated this game for the Prussians.

The first factor that held Frederick I back was the fear

of having his lands ravaged by war. With the Swedish main army in north

western Poland it was highly likely that Prussia would become their primary

target if Frederick I chose to side with the anti-Swedish coalition.

Furthermore, the solidarity between the members of the anti-Swedish

coalition had proven to be weak and Frederick had great fears of the

possibility of Saxony switching side if he declared war on Sweden. And it

was not much better if he sided with Sweden since the Russian main army was

deployed in Lithuania within striking distance from East Prussia. Prussian

observers, who had been shocked by the Russian’s brutal warfare in Livonia

and also the atrocities and widespread looting in supposedly friendly

Lithuanian territory, offered grave warnings about what could happen to East

Prussia if they engaged in a war against Russia. And also the core region

of Brandenburg was dangerously exposed to Saxon attacks since most of the

Prussian army was fighting in the War of the Spanish Succession.

The second factor that held Frederick I back was the fact

that he had ambitious goals in the west too. He had hoped to succeed William

of Orange as stadtholder of the Netherlands and also inherit his widespread

domains since he was his closest male relative. But when William of Orange

died in 1702 Frederick I was disappointed to learn that he had been left out

of his will and that the Dutch had no interest in making him their stadtholder. Nevertheless, he persisted with his claims to these

territories, and since his only leverage was the troops he supplied to the

allies in the Spanish war, this meant that pulling out of the war and

instead joining the Great Northern War would end all hopes of getting at

least some of William of Orange’s territories.

There were also financial reasons to stay out of the war

since Frederick I had greatly mismanaged Prussia’s economy. He was spending

half of the annual budget on the royal court alone in his vain attempts to

present himself as an equal to the other crowned heads in Europe. To

maintain their large army the Prussians were completely dependent on foreign

subsidies and these would be lost if Prussia withdrew its troops from the

War of the Spanish Succession. With the economy already in a poor shape, a

war would likely ruin Prussia.

Lastly there was also the fear of intervention from the

Maritime powers in case Prussia sided with the anti-Swedish coalition. The

Maritime powers certainly made such threats and the Prussians referred to

these in their negotiations with Denmark. But these threats may have merely

been used as an excuse to not take the step. The Danes got the same

treatment and were not as concerned about this, even though they too

frequently used this as an excuse in the talks with Russia and Saxony. The

Maritime powers were unlikely to intervene while the War of the Spanish

Succession was still in progress, because if they did that they would not

only lose valuable auxiliary corps but also effectively turn them into

French allies. However, if the War of the Spanish Succession would end

before the Great Northern War, then the Prussians (and the Danes) would risk

a repeat of 1679 when French intervention forced Denmark and Brandenburg to

return their conquests to Sweden.

All these concerns made Frederick I reluctant to join the

Great Northern War. What he really wanted to offer was friendly neutrality,

hoping that the mere threat of a Prussian entry in the war would make the

participants eager to overbid each other for Prussia’s friendship. He also

frequently tried to act as a mediator. A pet project of his was a compromise

peace in which the Polish commonwealth was partitioned so that Stanislaw

would get Lithuania and Augustus would get Poland proper. Frederick I pushed

this idea because he believed a partition would make it easier for him to

get a slice of Polish territory. But despite of the cautious nature of

Frederick I, his desire for territorial gains was so great that he would

join the war if the opportunity was too promising to ignore.

The first time it got close to a Prussian entry in the

war was in late 1704. Charles XII had left the vicinity of Prussia when he

headed south with his army to crack down pro-Augustus Polish forces. A Saxon

force behind his back then managed to seize Warsaw in a surprise attack.

This was Augustus first major victory and with the Russian main army in

Lithuania and Denmark eagerly waiting to join the war if Prussia did the

same, the great opportunity seemed to have arrived for Frederick I. Prussian

regiments which had recently fought in the battle of Blenheim were on their

march to East Prussia where a field army of over 18 000 men was to be

assembled. But a swift Swedish counter-offensive, resulting in the

re-conquest of Warsaw and the battle of Punitz, forced the Saxons and their

Russian auxiliary corps to seek safety in Saxony. Frederick I immediately

switched track and reassured Charles XII of his friendly intentions and that

the military build-up in East Prussia was motivated by fear of the Russians.

The second time was the winter of 1705-06 when the odds

appeared to be firmly stacked against Charles XII with large armies from

both West and East on course to squeeze the Swedish forces in Poland as well

as a sharp increase of the tension between Sweden and Denmark. Since few

Prussian troops were available at home at that time, a Prussian entry in the

war was not an immediate threat though, and the events of Fraustadt and Grodno would completely change the picture. Sweden emerged victorious and

was now even less interested in accepting Frederick’s territorial demands.

With Saxony under Swedish occupation the Prussians feared

that Sweden had effectively won the war and they blamed themselves for

missing such a great opportunity to gain territories by waiting too long to

pick a side. In 1707 Prussia finally signed a defensive alliance with Sweden

but the contents of that treaty was a far cry from what they once had hoped

for

Charles XII at the height of

his power

The Swedish invasion of Saxony in August/September 1706

forced Augustus to sign the peace of Altranstädt and end his participation

in the war. Since the Russian army was not perceived as strong enough to

resist the Swedish army on its own, it was widely believed in Europe that

the end of the Great Northern War was near. The assumption was that a

Russian campaign would be a very short affair since the Russians would

surely come to their senses and sue for peace once their army had

unsuccessfully clashed with the Swedes. Little did they know how determined

Peter I was to keep Saint Petersburg.

With the defeat of Russia a foregone conclusion, European

observers anxiously kept their eyes on what Charles XII planned to do with

his army that was now located deep inside German territory. The Danes in

particular feared that their provocations in the previous years would be

punished with a repeat of 1643-45 and 1657-58. Among many things, Danish

ships had traded in Swedish ports that were occupied by Russia, their

diplomats had spread lies about Sweden in European courts and most

importantly Danish troops had evicted the Holstein-Gottorp ruler of the

prince bishopric of Lübeck which Denmark claimed for one of their own

princes. Terrified about the possibility of a Swedish invasion the Danes now

folded on every issue of contention and agreed to all Swedish demands.

But to a much greater extent it was Austria who felt the

pressure from Charles XII. Their assistance to Sweden’s enemies during the

Polish campaign had not gone unnoticed, their last insult being that they

allowed Russian troops in Saxony to escape to Russia through Austrian

territory. However, it was Austria’s violation of the terms of the treaty of

Westphalia by persecuting Protestants in Silesia that caught Charles XII’s

special attention. He now demanded the immediate restoration of churches and

religious rights to the Silesian Protestants. The Emperor Joseph I refused

but Charles XII persisted and with that war looked like a serious

possibility.

The Austrian troops were fully committed in the War of

the Spanish Succession and the Emperor had nothing to stop Charles XII with

if he decided to invade the Austrian hereditary lands. Furthermore, the

Emperor received no sympathy from his Protestant allies who strongly urged

him to accept the Swedish demands. Not even Sweden’s former enemies were

interested in an Austrian alliance. Denmark refused on the grounds that

Austria’s military was too weak for it to be a useful ally, and Augustus was

actually hoping to join Sweden in case of a Swedish-Austrian war. Only

Russia encouraged Austria to go to war against Sweden, but their offer of a

40-50 000 men strong auxiliary corps to aid the Austrians was deemed to be

of little value.

Isolated and with few troops to defend him, Joseph I

reluctantly accepted the Swedish demands in the second treaty of Altranstädt

in August 1707. When the pope sent an angry letter in which he complained

over the fact that a Catholic monarch had given in to religious demands from

a heretic, Joseph responded by stating that the pope should be grateful that

Charles XII had not demanded that the Emperor should convert to

Protestantism because in that case he would not have known what to do.

With the affair of the Silesian Protestants settled

Charles XII could finally march east to confront the Russians. In his year

long absence the Russians had occupied all of Poland and undermined

Stanislaw by supporting the pro-Augustus Polish forces. Even though Augustus

had officially abdicated, his faction continued to resist Stanislaw, whom

they viewed as an illegitimate Swedish puppet, and claimed that the Polish

throne was now vacant. Peter I strongly encouraged this faction to elect a

new pro-Russian king but they did not want to align themselves too closely

to Russia since Charles XII was expected to come back to Poland in which

case a reconciliation with Stanislaw’s faction might be necessary.

Augustus the Strong and Charles XII have dinner together in Altranstädt December 1706

Augustus at the lowest point

in his reign

Another complication in the Polish civil war was that

Augustus had not given up on his Polish throne and he maintained contacts

with his former supporters to encourage them to continue resisting

Stanislaw. During the Russian campaign he repeatedly promised that he would

soon intervene in Poland with Saxon troops if they just kept on fighting.

But these promises were not sincere. He also promised Peter I to capture

Charles XII while he was in Saxony and then deliver him to Russia. But he

did not do so even when Charles XII made a surprise visit to him in Dresden

without an armed escort. And even though he also ensured the Russians that

he intended to re-join the war as soon as possible, he managed to stall the

negotiations by insisting on more subsidies and more auxiliary troops than

Russia was willing to give.

The reality was that Augustus, just like everyone else,

was very sceptical of Russia’s chances to win the war. And Saxony was

effectively bankrupt after years of warfare and a long Swedish occupation so

he could not afford to gamble on a new war. But true to form, Augustus

wanted to keep all options open just in case Charles XII’s luck would

change, so he kept on negotiating in bad faith and making promises he did

not intend to keep.

However, Augustus being the man he was, an imaginative

opportunist with unbridled ambitions, meant that even in this dark period in

his reign he still pursued great projects. With his prospects in the East

looking dim he instead turned his eyes to the West. Since he was a

descendant to the 13th century ruler of Both Sicilies, Frederick

II, he laid claim to the kingdom of Naples which was a part of the Spanish

inheritance. It was this kingdom he had hoped to gain if Charles XII had

attacked Austria. Since Charles XII instead turned to Russia, Augustus

switched camp and sent auxiliary troops to the Maritime Powers in the vain

hope that they would support his claim to Naples. And if that was not enough

he also claimed the Spanish Netherlands as compensation for the Holy Roman

Empire’s failure to protect him from the Swedish invasion. These demands

were completely unrealistic, but nevertheless he made a serious effort to

convince the Great Powers that he should gain these lands. It was as if he

believed there was no limit to what he could achieve by exploiting his great

talent in manipulating people.

The tide turns

It was Denmark’s plan to join the Great Northern War

again once the Swedish main army was at a safe distance from them. But they

also needed to be reassured that Russia was actually going to continue the

war and not sue for peace in the event of a defeat, such as the battle of

Holowczyn in July 1708. The Danes also negotiated with Russia about the size

of the subsidies and auxiliary corps that Russia had to provide to gain them

as an ally. And just like in the Saxon negotiations the demands were too

high for the Russians to accept. But Denmark was not in a hurry and their

king Fredrick IV could afford himself a long Italian vacation from October

1708 to the summer of 1709 which greatly slowed down the speed in the

negotiations. Frustrated with this, Russia sent a diplomat to Venice in

January to negotiate with the king in person. The battle of Lesnaya and

Charles XII’s march south to Ukraine had offered a great opportunity for

Denmark to intervene, and the Russian diplomat proposed that the king

immediately signed an alliance so that Denmark could join the war in June.

Frederick IV refused however and still insisted on huge subsidies from

Russia if he was to enter the war.

Augustus on the other hand felt greater pressure to join

the war than Denmark. With the news of the battle of Lesnaya as well as

reports of military setbacks for Stanislaw’s forces in late 1708, the time

for action came closer in great speed. His Polish supporters threatened to

elect someone else as king if he did not make good on his promises.

Augustus’ problem however was the impoverished state of Saxony. He really

needed subsidies and auxiliary corps from Russia as well as other allies in

order to challenge the Swedish forces in Poland. This meant a lot of work

for the Saxon diplomats during the spring and summer of 1709.

In order to not provoke intervention from the Great

Powers both Denmark and Saxony would pursue the strategy of keeping the war

outside of North Germany, preferably through a formal treaty by all

participants in the war. This would also have the obvious advantage of

keeping Saxony safe from Swedish invasion as well as protecting Denmark’s

southern border. From the Swedish point of view neutrality in North Germany

was a mixed bag which would later cause a lot of friction between Charles

XII and the government in Stockholm. But in 1709 Sweden was still kept out

of the loop in these discussions and North German neutrality was primarily a

way for Sweden’s enemies to appease the Great powers. This affected the

military planning in such a way that Denmark would not attack

Holstein-Gottorp or Sweden’s German provinces when they re-entered the war

and instead invade Scania. A negative effect of North German neutrality was

however that Hanover and Prussia would be less likely to join the

Anti-Swedish coalition if Sweden’s German provinces were off limit.

Nevertheless, Augustus approached both Hanover and

Prussia in February of 1709 in the hope of gaining them as allies. Hanover

was however very much opposed to a war against Sweden and could not be

tempted with the prospect of gaining Bremen-Verden from Sweden. But Augustus

was still encouraged by the fact that they promised to remain neutral so

long Saxony did not disturb the peace in North Germany.

Prussia was on the other hand much more interested in an

anti-Swedish alliance despite the fact that Prussia had signed an alliance

with Sweden as late as 1707. They had actually begun to undermine

Stanislaw‘s rule in Poland already in December 1708 when news of the battle

of Lesnaya arrived, although they preferred that the Poles elected someone

else than Augustus as king.

In a rare moment of decisiveness Frederick I proposed to

the Saxon diplomat in April a plan that would give Scania to Denmark, Saint

Petersburg to Russia, Bremen-Verden to Hannover and Hesse, and Livonia to

Stanislaw. Poland would be divided between Prussia and Augustus so that

Prussia got Polish Prussia, Ermland and Courland. To make this happen

Prussia offered to participate in the war with 50 000 men. Frederick I

rescinded the offer just a week later though and urged the Saxons to

postpone the war. As had happened many times before, Frederick I was

conflicted between his ambitions in the West and the East. It was the

possibility that the War of the Spanish Succession was about to end soon

that discouraged Frederick I from withdrawing his troops and thus lose any

prospect of gaining territory in the West.

When it became clear that the war would not be postponed

Frederick I returned to his old attempts to gain territories by only

offering friendly neutrality in exchange. But just like before no one was

willing to pay so much for so little. Even without such outrageous demands,

Augustus was never very enthusiastic about the idea of having Prussia as an

ally. He regarded Prussia as Saxony’s greatest rival and did not want that

state to be enlarged, and certainly not through the acquisition of Polish

territory.

The need for a Prussian alliance was also greatly reduced

when the Danish king arrived from his long Italian vacation to Dresden in

late May and began serious negotiations. A Danish-Saxon offensive alliance

was then signed 28 June which would take effect if Russia joined it before

September. The September deadline was intended to force Russia to agree to

large subsidies and auxiliary corps. Prussia was also asked to join but

Frederick I would only commit to a minor treaty in July which would prevent

Swedish troops from marching through Prussian territory. The Danish-Saxon

treaty also appeased the Great powers by not only declaring support for

North German neutrality but also by promising to not withdraw any troops

from the War of the Spanish Succession.

If everything went according to the plan, Saxony would

invade Poland in September and Denmark would open two fronts in Scania and

along the Norwegian border in November. What they did not anticipate however

was the complete destruction of the Swedish main army less than two weeks

after the treaty was signed. The battle of Poltava did not just change the

balance of power between Sweden and its enemies, it also changed the balance

of power inside the re-emerging Anti-Swedish coalition in a very drastic

way.

The Restoration of the

Anti-Swedish Coalition

The news about the battle arrived in Dresden 24 July and

the Russian diplomat used this to put immense pressure on Augustus. The Tsar

would not offer more subsidies and auxiliaries than he had done previously

and Augustus had to start the war before the month of August if he wanted to

receive even that. This meant that Augustus was forced to start a war before

the tsar could ratify the treaty and he could then only rely on the goodwill

of Peter I if any subsidies at all would be sent to Saxony.

Augustus did sign the treaty on 29 July and in doing so

he agreed to immediately invade Poland with at least 10 000 men. However, a

complication was the fact that Augustus did not have 10 000 men at his

disposal. He was also not sure about the size of the forces opposing him in

Poland and there were even rumours that Charles XII was about to enter

Poland with a 50 000 men strong Tatar army under his command. Add to that

the Swedish troops in Germany and Augustus position appeared to be anything

but secure. He therefore delayed his invasion until late August and in the

meantime he tried unsuccessfully to convince Denmark to attack

Holstein-Gottorp, and Hanover to attack Bremen-Verden. It was not until the

Russians threatened to put someone else than him on the Polish throne that

he relented and on 24 August finally crossed the Polish border. His army was

however still well below 10 000 men, so he carefully avoided battle with the

Swedish forces and thus allowed them to safely evacuate Poland for Pomerania.

All this greatly angered the Russians who had also invaded Poland and hoped

to capture another Swedish field army.

In the end Augustus would not get any subsidies from

Russia and while he did reclaim his Polish throne, real power in Poland,

political as well as military, was now in Russian hands. Requests from both

Augustus and the Poles to reduce the Russian military presence were bluntly

denied. Those Poles who had opposed Stanislaw by accusing him to be a

Swedish puppet now found themselves being ruled by a Russian puppet instead.

But despite of all this friction a Russian-Saxon alliance was signed in

October which promised Livonia to Augustus. Russia would however not hand

over Livonia to Augustus when it was conquered and it was most likely never

Peter I’s intention to do so either. Livonia was merely used as an incentive

to keep Augustus allied to Russia and give military support to their

campaigns.

Russia’s hardball tactics were also used against Denmark

who now found that Russia was not willing to give any subsidies or

auxiliaries at all for them to re-enter the war. Denmark too was racing the

clock since the destruction of the Swedish main army in Ukraine meant that

most of these regiments would be restored in Sweden. If Denmark waited to

the spring of 1710 to begin the war, then they would face a fully restored

Swedish main army with a whole winter of military training behind it.

Furthermore, the Russians made the Danes believe that a Swedish-Russian

peace treaty may be concluded if they did not hurry. So the Danes too signed

a treaty with the Russians in October with none of the benefits that had

been offered to them just a half year before.

In early November the Danes invaded Scania and faced

little initial opposition. But even though Denmark had waited many years for

the right opportunity to launch this attack, their preparations were not

satisfactory. The Norwegian army was not ready to launch a diversionary

attack during the winter as originally intended, so the Swedes could

withdraw regiments from the Norwegian border to confront the Danes in Scania.

And despite of strong objections from their field commander, the Danish

government insisted that their army should advance and capture as much

territory as possible rather than attempting to seize a fortress. The flat

terrain of Scania meant that when winter came and the rivers froze to ice,

there would be no natural line of defence against the Swedish

counteroffensive. When this happened the Danish army had no choice but to

concentrate its forces and meet the Swedes in a pitched battle, which they

then lost decisively.

Had the Swedish commander Magnus Stenbock decided to

storm the city of Helsingborg, where the Danes had retreated after the

battle, then the entire Danish field army would have been destroyed and

Denmark would most likely have sued for peace, making their second attempt

just as short as the first one. Even after the successful evacuation of

their army from Helsingborg, the Danish court was still in a state of shock

and would have immediately sued for peace had the Swedes made any moves that

suggested an invasion of Sealand was imminent. Unfortunately for Sweden, the

man who recognised great opportunities like this was far away in the Ottoman

Empire. Magnus Stenbock received a promotion to field marshal by the Royal

council in Stockholm for his victory but Charles XII retracted that

promotion on the ground that he should have destroyed the Danish army by

storming Helsingborg. He also ordered the council to offer a favourable

peace to Denmark believing that the battle had made them regret their

re-entry in the war. However, it took the news nearly two month to reach

Bender where Charles XII was staying, and by the time the Swedish government

could act on his orders the Danes had already calmed down and were now

determined to continue the war. This time the Anti-Swedish coalition

remained intact after the initial setback.

The Prussian Epilogue

The potential fourth member of the coalition did not

materialise this time either since Prussia continued to waver and make

unrealistic demands. In August 1709 Frederick I heard rumours that Charles

XII had died and he ordered that Swedish-held Elbing was to be taken with

force by Prussian troops if the rumours were confirmed. But even though the

Prussian troops were well prepared and the commander reported that the task

could be done with relative ease, Frederick I insisted that Charles XII had

to be dead before he would commit to this act of war against Sweden. When it

was clear that Charles XII was still alive, Frederick I tried unsuccessfully

to convince the Swedes to hand over Elbing to Prussia before it fell to the

Russians.

Frederick I also contacted Russia and offered all kinds

of support to them, except military, in exchange for Elbing. Russia was

interested and in late September Peter I offered to give Elbing to Prussia

if they contributed with artillery pieces and ammunition to the siege.

During this time Frederick got increasingly bolder and demanded more Polish

territory from the Russians and contemplated an attack against Swedish

Pomerania. The Russians did not dismiss his territorial demands but they

wanted to wait with an agreement until Frederick I and Peter I met in person

in Marienwerder in late October. By that time Frederick’s territorial

demands now consisted of Swedish Pomerania, Polish Prussia, Ermland,

Courland and Samogitia. But amazingly enough he insisted in gaining all

these vast territories without giving anything in return except for friendly

neutrality. The Swedish army in Poland had just before the meeting evacuated

to Pomerania and this had apparently made Frederick too afraid to attack

that province. The Russians were baffled and could initially not believe

that it was even possible that the Prussians were serious with these

demands. But once they realised that these really were Prussia’s terms, the

Russians promptly rejected them and instead agreed to a treaty that was just

as meaningless as the one Prussia had signed with Denmark and Saxony in

July.

Frederick I left the meeting bitter, sad and humiliated.

He then threw a temper tantrum and blamed everyone in his surrounding for

this setback. But it was due to his own shortcomings that he had missed a

golden opportunity to enlarge Prussia. The 19th century Prussian

historian Droysen famously described Frederick’s failed foreign policy with

the phrase: “in the West: war without politic, in the East: politic without

an army”. Eventually Prussia would join the Anti-Swedish coalition and gain

territory, but that was during the reign of Frederick’s much more able son

Frederick William.

|