|

Örjan Martinsson

| |

|

(Royal Majesty's Life Guard on Foot)

The Swedish infantry

was a formidable force during the Great Northern War and its most

distinguished regiment was Charles XIIs own guard regiment, the Livgarde.

This unit's elite status was acknowledged by their higher wages and hats

laced with gold, silver and silk. It was also, with first 1,800 men and

later 2,600 men, the by far largest regiment in the Swedish army.

In each battle the Livgarde took the lead and in the battle line they held

the place of honour furthest to the right.

The Livgarde

has won numerous victories in most of Sweden's war but there is no doubt

that its heydays were during the Great Northern War. Because in this war

they took part in the landing at Humlebæk in 1700, the battle of Narva in 1700,

the crossing of the Düna in 1701, the battle of Kliszow in 1702, the siege of Thorn

in 1703

and the battle of Holowczyn in 1708. However, after all these successes they suffered a crushing defeat at Poltava

in 1709

and only half of the Livgarde remained when the Swedish army surrendered at Perevolochna

three days later.

The Livgarde was restored after the disaster but the new guard would not

experience any triumphs as the old one had done. Recruitment problems kept

it as a garrison regiment in Stockholm until 1718 when it participated with almost full

strength in Charles XII's last campaign in Norway.

|

|

Organisational History of the Livgarde 1618-1792

The original

role of the Livgarde was to be the king's bodyguard and since kings in all

ages have had bodyguards it is possible to trace the lineage of the Livgarde

all the way to Gustav

Vasa's rebellion in 1521. However, in practise there were several different

guard regiments during Sweden's age of greatness (1611-1718), which for

various reasons disappeared and were replaced by new regiments. To be exact

there were four incarnations of the Livgarde during this period, created in

turn by Gustav II Adolf,

Kristina, Charles XI and Charles XII. The continuity that existed between

these regiments was the small force that was always left in

Stockholm to guard the palace while the rest of the regiment went on

campaign.

The Drabant

Corps that had protected the kings of the Vasa dynasty was in 1618

transformed into a company in a five year old mercenary regiment which Gustav II Adolf

elevated to be "Konungens

livregemente" (the King's Life Regiment). It would also be called

Hovregementet (= the Court Regiment) or Gula regementet (the Yellow

Regiment, after the colour of their uniforms). The original drabants

retained however a special status by consisting of Swedes and being called

the king's Livgarde (Life Guard). The rest of the regiment consisted of

Germans. After participating in Gustav II Adolf's campaigns in Livonia, Prussia

and Germany the regiment was split up after the battle of Lützen 1632. The Livgarde escorted

the king's dead body to Stockholm and stayed there as a palace guard. The

remaining part, which was now only called the Yellow Regiment, continued to

fight in Germany and went 1635 into French service when its commander

Bernhard of Weimar defected from the Swedish army.

The

Livgarde Company in Stockholm, which 1638-44 had the colonel of Södermanland

Regiment as its captain, was expanded during the war against Denmark 1643-45 to

become an independent regiment of 20 companies. This incarnation of the

Livgarde was however almost never together but usually distributed on

different garrisons and theatres of war. This state of affairs did not

change after the Peace of Westphalia 1648 when the Livgarde was reduced to 12

companies. After the death of Charles X Gustav in 1660 the Livgarde was

split in a way that was similar to what happened in 1632. It was reduced to

one company which served as a palace guard in Stockholm and eight companies

which garrisoned Riga until 1672 and then Pomerania. The latter part came to

be known as the German Guard and lived a life of its own. Finally in 1680 it

formally ceased to be a part of the Livgarde when it was transferred to

garrison Scania and Halland with the name Tyska livregementet till fot

(German Life Regiment on Foot). It was transferred to the German provinces

in 1709

and was lost 1715 when these fell to the enemy.

The king's

bodyguard or Livgarde always included a number of mounted soldiers until

September 1700

when Charles XII detached them to create the independent Drabant Corps.

With this Livgardet till häst och fot (Life Guard on horse and foot)

changes its name to Livgardet till

fot.

The company which

guarded the Royal Palace in Stockholm

after 1660 (consisting both of foot soldiers and mounted drabants)

represented the nucleus of the third incarnation of the Livgarde. When

Charles XI came of age in 1672 he expanded the

Livgarde to four companies and as a result of the Scanian War it was further

expanded to twelve companies in 1676. This organisation (ten companies of 150 men

and two companies of 200 men, a total of 1,900 men) would remain in place

until the outbreak of the Great Northern War. All companies then became 150 men

strong because 100 men were left in Stockholm as a palace guard when the

Livgarde marched to war in April 1700. However, already in September the

same year the Livgarde was yet again reorganised. Charles XII wanted to

increase officer density by redistributing the privates on 18 companies,

each with a strength of 100 men. This organisation also included for

the first time separate grenadier companies, There were three of these and

under the command of a grenadier major they formed a grenadier battalion.

Ever since 1684 the Livgarde had had an increasing number of grenadiers and

in 1703 this establishment was doubled to six companies. In 1702 the Livgarde

had also been strengthened with three regular companies and since 1701

every company was 108 men strong. All this meant that from August

1703 the Livgarde had an establishment of 24 companies with 108 men

each which formed four battalions (one of them a grenadier battalion). At

full strength the Livgarde counted 2,592 men (not including the palace guard

in Stockholm).

| |

Rank-and-File in

the Field Regiment |

Number of Companies |

Officers & NCOs |

Palace Guard

(officers/NCOs + Rank-and-File) |

|

April 1700 |

1,800 |

12 with 150 men each |

106 |

7 + 100 |

| Sept. 1700 |

1,800 |

18 with 100 men each |

150 |

7 + 100 |

| 1701 |

1,944 |

18 with 108 men each |

169 |

7 + 100 |

| 1702 |

2,268 |

21 with 108 men each |

196 |

9 + 120 |

| 1703 |

2,592 |

24 with 108 men each |

223 |

9 + 120 |

| 1707 |

2,592 |

24 with 108 men each |

247 |

9 + 120 |

|

1714 |

2,736 |

24 with 114 men each |

296 |

12 + 126 |

|

In addition each company had two drummers an one piper. |

After the

Livgarde had been annihilated in Ukraine 1709, Charles XII ordered that it

be restored to its former strength and additionally augmented by six mounted

"furirskyttar" in each company (a total of 2,736 men, not including

the palace guard). But for various reasons the recruitment for this fourth

incarnation was very slow (read more about this below) and it was only after

Charles XII's return to Sweden in December 1715 that it took off. Although

this work came to nothing due to catastrophic losses during the poorly

executed retreat from Norway after the death of Charles XII.

The ambition

level of the reconstructed Livgarde was lowered in May 1722 to 18 companies

(of which three were grenadier companies) with a total strength of 1,800

rank-and-file. Although this established strength was not reached until

1728. The year before, however, the Parliament had decided that the Livgarde

would return to the establishment of 1696 and that the manpower would thus

be divided into only twelve companies. This meant fewer officers, but the

reduction of the officer corps was to be gradual by not hiring replacements

for those who left on their own accord. And the companies were withdrawn

only when their captain had left his post. This would take a very long time

as the Livgarde already had a large number of redundant officers as a result

of the previous reduction in regimental strength and the wartime doubling of

officers. However, the organisation with 18 companies was restored in 1737

and it would then remain until 1790.

In 1788 the

manpower was increased to 113 men per company and two years later it was

further increased to 120 men. Although in 1790 a Second Guards Regiment was

also created, which meant that the original Guard, which was now called the

First Guards Regiment, was reduced to ten companies. Thus, the total

manpower was only 1,200 men.

The organisational changes continued during the Gustavian period, but these

and the later ones are not covered here. However, it is worth mentioning

that the regiment was renamed Svea Livgarde in 1792 and that the

original short name was not taken back until after a regimental merger in

2000.

Regimental

Commanders and Battles

Listed below are the regimental commanders of the Livgarde during Sweden's Age

of Greatness and up to 1790 when the Guard came to consist of two regiments. It also includes all the battles which the

regiment participated in during this period. Green

colour represents victories, red colour defeats

and

black colour indecisive battles.

|

|

Yellow Regiment |

|

1618-1625 |

Philipp

Johan von Mansfeld |

1621

Riga |

|

1625-1627 |

Frans Bernhard von Thurn |

1626 Wallhof |

|

1627

Dirschau |

1627-1631

|

Maximilian von Teufel

(killed at Breitenfeld) |

1629 Gurzno

1631 Frankfurt an der Oder

1631

Breitenfeld |

1631-1632

|

Nils Brahe

(mortally wounded at Lützen) |

1632 Lech (Rain) |

| 1632 Alte Veste |

| 1632

Lützen |

|

1632-1634 |

Lars Kagg |

1633 Oldendorf |

|

1634-1635 |

Wulf von

Schönbeck |

1634 Nördlingen |

|

|

Kunglig Majestäts livgarde |

|

1635-1635 |

Thure Liljesparre |

|

1636-1638 |

Didrik Yxkull |

|

1638-1644 |

Caspar Otto Sperling |

|

1644-1652 |

Magnus Gabriel De la Gardie |

|

1652-1653 |

Jakob Casimir De la Gardie |

|

1653-1654 |

Christoffer Delphicus Dohna |

|

1654-1660 |

Carl Christoffer Schlippenbach |

1656

Warsaw

1658 March Across the Belts |

| 1659

Copenhagen |

|

Feb-Dec.

1660 |

Nils Brahe |

|

1660-1664 |

Gustaf Adam Banér |

|

March-Sep.1664 |

Carl Larsson Sparre |

|

1664-1668 |

Axel Julius De la Gardie |

|

1668-1673 |

Gustaf Lillie |

|

1673-1677 |

Christoffer Gyllenstierna |

1676

Halmstad

1676 Lund

1677 Landskrona |

|

1677-1686 |

Jakob Johan Hastfer |

|

1686-1696 |

Bernhard von Liewen |

|

1696-1706 |

Knut Posse |

1700

Humlebæk

1700 Narva

1701 Düna

1702 Kliszow |

|

1706-1712 |

Carl Posse

(in Russian captivity from 1709) |

1708

Holowczyn |

| 1709

Poltava |

|

1712-1717 |

Gabriel Ribbing (in Danish captivity 1711-1713) |

|

1717-1727 |

Michael Törnflycht |

|

1727-1739 |

Arvid Posse |

|

1739-1744 |

Otto Reinhold Wrangel af Sauss |

|

1744-1751 |

Adolf Fredrik of Holstein-Gottorp |

|

1751-1756 |

Per Gustaf Pfeiff |

|

1756-1772 |

Fredrik Axel von Fersen |

|

1772-1792 |

Gustav III |

1790

Svensksund |

Note that of the battles fought in the period 1621-1635, only Lech and

Lützen are recognised as victories for the Livgarde. Presumably it is

because the Yellow Regiment fought these battles without the participation

of the part of the regiment that was sent back to Stockholm in 1632 and from

which today's Livgarde originates. Nor is the landing at Humlebæk included

among the official victories.

The main part of the Livgarde participated in both the Russian War in

1741-43 and the Pomeranian War in 1757-62 but was not involved in any major

engagements. A more important event was instead the Livgarde's involvement

in a planned coup attempt in 1756, which was however revealed and resulted

in the regimental commander being forced to retire.

|

|

Great Northern War

For the

Livgarde, the Great Northern War started on 25 April 1700 when they left

Stockholm and began a march to Malmö where they arrived on 11 June. They

then became a part of the main army and remained so until the Battle of

Poltava in 1709 and distinguished themselves as an elite regiment. After the

capitulation at Perevolotjna, however, its glory days were over and the

great difficulties with restoring the Livgarde meant that for a long time it

was not an unit fit for fight. Instead of campaigning against Sweden's

enemies, it had to stay at home in Stockholm as a garrison unit until

Charles XII's return to Sweden resulted in much more forceful recruitment.

It was a very capable Livgarde, albeit poorly dressed, which then took part

in Charles XII's Norwegian campaign in 1718. However, the retreat from

Norway was another death blow for the Livgarde which had to be reconstructed

again while it remained at home as a garrison in Stockholm.

The table below gives a detailed picture of the Livgarde's movements during

the war and its losses in the various battles:

|

1700 |

|

During the landing at

Humlebæk on 25 July, three guardsmen were killed and 18 were wounded.

In addition a lieutenant was also killed and two NCOs were wounded.

In the battle of Narva on 20 November, 132 privates and NCOs were

killed, 170 men were wounded. The officer's casualties were six killed

and 15 wounded. |

|

April-June |

March Stockholm-Malmö |

|

July-Aug. |

Campaign in Zealand |

|

Aug.-Sep. |

Scania-Blekinge |

|

Oct.-Nov. |

Campaign in Estonia |

|

December |

Winter quarters in Estonia |

1701 |

In the battle of Düna on 9

July, 19 privates were killed and 73 were wounded. The casualties for

officers and NCOs were 4

killed and 8 wounded. |

|

Jan.-June |

Winter quarters in Estonia |

|

July |

The crossing of the Düna |

|

Aug.-Dec.. |

Operations in Courland |

1702 |

In the battle of Kliszow

on

9 July, 54 privates and 12 officers and NCOs were killed. It was

reported that 6

officers were wounded. |

|

Jan.-June |

The invasion of Poland |

|

July |

Battle of Kliszow |

|

Aug.-Sep. |

Stay at Krakow |

|

Oct.-Dec.. |

March Krakow-Sandomierz |

1703 |

The map above shows

the movements of the Swedish armies during the Russian campaign

1707-1709. The Livgarde was part of the main army, but Lewenhaupt's

corps contained 3-männing soldiers and these were used to fill the

ranks of the Livgarde when they joined the main army. |

|

Jan.-May |

Winter quarters at Sandomierz |

|

May-Oct. |

The siege of Thorn |

|

Oct.-Dec.. |

Winter quarters in West Prussia |

1704 |

|

Jan.-May |

Winter quarters in West Prussia |

|

June-Sep. |

March West Prussia-Lemberg |

|

Sep.-Dec.. |

March Lemberg-Jutrosin |

1705 |

|

Jan.-July |

Winter quarters at Jutrosin |

|

July-Aug. |

March Jutrosin-Błonie |

|

Aug.-Dec.. |

Stay at Błonie |

1706 |

|

Jan.--March |

The blockade of Grodno |

|

April |

March Grodno-Pinsk |

|

May |

March Pinsk-Jarosławiec |

|

June |

Stay at Jarosławiec |

|

July-Aug. |

March Jarosławiec-Saxony |

|

Sep.-Dec.. |

Winter quarters in Saxony |

1707 |

|

|

Jan.-Aug. |

Stay in Saxony |

|

September |

March Saxony-Sokolnik |

|

October |

Stay at Sokolnik |

|

November |

March Sokolnik-Wlosawek |

|

December |

Stay at Wlosawek |

1708 |

|

In the battle of Holowczyn,

69 NCOs and privates were killed. The wounded were 485.

Officer casualties were 40 men. The high number of wounded in relation

to the killed is said to have been due to the Livgarde wading across

a river. This resulted in wet uniforms making it more difficult for

bullets to penetrate and thus fewer injuries that became fatal.

|

|

Jan.-Feb. |

March Wlosawek-Smorgon |

|

Feb.-May |

Stay in Lithuania |

|

June |

March to Holowczyn |

|

July |

Holowczyn & stay in Mogilev |

|

Aug.-Sep. |

Tatarsk, march to Severia |

|

Oct.-Dec.. |

March Kostenitji-Romny-Hadjatj |

1709 |

|

In the battle of Poltava

on

28 June, 24 officers were killed, which was almost a quarter of the

corps. In addition, 59 officers were captured (19 at Poltava, 30 at

Perevolochna and 10 at an unknown location). Of these, 25-33% were

wounded. Two Russian sources, which are not entirely reliable, state

that either 1,350 NCOs and privates, or alternatively 121 NCOs and

1,196 privates were captured at Perevolochna. Since the Livgarde

probably had a strength of about 2,500 men before the battle, this

would mean that half were killed or captured on the battlefield at

Poltava. |

|

Jan.-April |

March Hadjatj-Poltava |

|

April-June |

Siege of Poltava |

|

June |

Battle of Poltava |

1709-18 |

Garrison in Stockholm |

1718 |

|

|

Sep.-Oct. |

March Stockholm-Dalsland |

|

Nov-Dec. |

Campaign in Noway |

|

December |

Return march to Sweden |

Recruitment of the Livgarde

Together with the Artillery Regiment and the Adelsfana, the Livgarde was one

of the few truly national regiments which collected its recruits from all

over Sweden.

However, the Livgarde consisted almost exclusively of ethnic Swedes. The

guardsmen who came from Finland were for example concentrated to its Swedish

speaking regions. And despite of the strong national character the main

recruitment area can be localised to the central portions of Sweden (Svealand

and Östergötland) from where about 75 % of the recruits came.

The number of Stockholmers in the ranks was high but since most Swedes at

this time lived on the country side their share was not higher than 9 %.

A guardsman had a wage of 36 daler in silver the year 1696

(to be compared with the 33 daler which soldiers received in other enlisted

infantry regiments in proper Sweden). If he was promoted to underrotmästare

(= vice filemaster) he would get 41 daler. A rotmästare (filemaster)

received 50 and corporals got 63-66

daler. The lower NCO ranks (förare, furir &

rustmästare) received 90 daler in silver as their yearly wage while the

higher NCO ranks (fältväbel & sergeant) got 108. Lieutenants &

ensigns earned 378 daler, captains 556, the major 1,242, the lieutenant

colonel 1,306

and the colonel

2,056 daler. The income differences were enormous and even though the

private guardsmen earned more than their colleagues they could not support a

family on that wage. It was almost required that the soldier had a second

job and/or a wife who also worked. Because the burdens of military service

were light during peace time these second jobs could very well be the

soldiers' primary occupation.

When the Guard was overseas during the Great Northern War it was intended

that the recruitment was to be managed in such a way that each provincial

governor had a quota which they should recruit and send to the Livgarde. But

the first contingent of the governors recruits was far from the desired size

and not all of them met the requirement for service in the Livgarde.

Of the 510 men which the governors were to recruit only 250 of them were

actually added to the ranks in 1701 and not rejected at arrival. The

recruitment was thereafter centralised and this task was given to lieutenant

colonel Åke Rålamb. But the numbers did not increase and in 1702 only 285 recruits

arrived, followed by 190 men in 1703, 118 men in 1704 and 156 men in 1705.

The 1706 contingent (which arrived in

1707) consisted of 117 men and the 1707 contingent was 203 men strong. The 1708

contingent which arrived too late to Riga to join the main army consisted of 332 men

which were called back to Sweden in 1709. Rålamb managed to recruit 79 men to the

1709 contingent before he lost this assignment to the interim commander of

the restored Livgarde.

Since the recruits were not sufficient to fill the ranks of the growing

Livgarde, the King arranged for soldiers to be transferred from other

regiments. One company each from Tyska, Svenska and Drottningens

livregemente were ordered by the King in October 1701 to be transferred

to the Livgarde (these regiments garrisoned fortresses in Scania and the

Swedish west coast). In 1703

one battalion each from Uppland and Östgöta-Södermanland 3-männing regiments

were merged with the Livgarde (the former also included soldiers from the

provinces of Dalarna and Västmanland. An additional company each from

Svenska and Drottningens

livregemente were added the same year and in the next year 150 men from

Jämtland's Regiment was added to the Livgarde. Finally during the Russian campaign in

1708 the rest of these 3-männing regiments together with Småland and

Närke-Värmlands 3-männing regiments were merged with the Livgarde (altogether

approx. 1,000 men). Småland's 3-männing regiment had contributed 72

men to the Livgarde as early as September 1700, when a sharp increase in the

number of officers through promotions within the Livgarde had resulted in

vacancies.

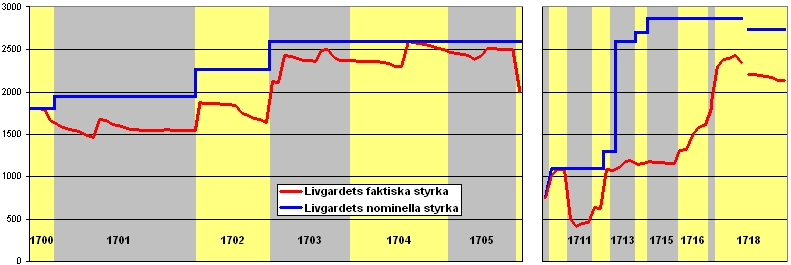

Strength of the Livgarde during the Great Northern War.

Nominal strength in blue and effective strength in red.

The period 1707-09 is missing because

the source material was lost in the capitulation at Perevolochna. The lines are

broken for the year 1718 because the company that was left in Stockholm is not included in the second

half of that year.

When the remnants of the Livgarde field regiment capitulated in at Perevolochna 1709

there were, counting the palace guard (120 men strong since 1702) and the

existing recruits, a force of about 600 guardsmen in Stockholm. These were

organised into new companies and the work to restore the Livgarde began.

However, the recruitment progressed at a slow pace and the organisation

consisted of just twelve companies for a long time. An important reason why

things went slowly in the beginning was a lack of initiative on the part of

the elderly governor of Stockholm, Knut Posse, who was most responsible for

the Livgarde's recruitment. It certainly did not

help either that the plague in 1710 killed 60 % of the then 1,000 men strong Guard.

Only 419 men remained at the muster in June 1711, and among them there

were several

palace guards who had been to old for field service already in 1700 (these

men included a 90-year old man who was discharged the following year).

Conscription of men from the mining region of Bergsslagen (previously exempt

from recruitment) helped to recover the Livgarde's strength but then for a

long period the strength stood still at 1,000 men.

Some of the difficulties with the recruitment can be explained by the fact

the lega (the amount of money the recruit was given directly when he

signed the contract) was only 20 daler of silver,

which made the Livgarde less attractive compared to other regiments. The men

who recruited for the Livgarde had to compete with all the rotebönder

(farmers tasked with recruiting one infantry soldier) and rusthållare

(men tasked with recruiting one cavalryman and horse) who at the same time

were searching for recruits to restore the provincial regiments. The

conditions in the soldiers market thus required (according the regimental

commander Ribbing) a lega of at least 33.33 daler in silver.

This request of raising the lega was however rejected by the royal

council on the ground of the poor financial state of the Crown. The

troubling economy also meant that salary payments were very irregular and

that the guardsmen often lived in misery. This, of course, made it even more

difficult to attract recruits to the Livgarde.

All this changed when Charles XII returned to Sweden in December 1715 and

could now personally deal with the restoration of his Livgarde. The

Livgarde's recruiters had already made themselves known for their hard-line

persuasion methods before then. But now a determined hunt began for men who

lacked employment, students who did not study diligently, and occupational

categories that were considered non-essential in time of war. The notion

that recruits were supposed to be volunteers was set aside and, without

sacrificing quality, the Livgarde's manpower increased so rapidly that it

was 2,200 strong when the Norwegian campaign began in 1718. But even this

work came to naught as a result of external circumstances. The king's death

led to an unplanned retreat to Sweden in the middle of winter. The Livgarde

also had the misfortune of marching last, so that those food storages that

did exist along the march route were empty when the Livgarde got there. The

result was a disaster and of the only 795 remaining guardsmen who were

mustered in Stockholm in 1719, half had to be discarded as unfit for

continued service.

By disbanding temporary regiments and transferring the men to the Livgarde,

its strength was able to recover so that in October 1720 it numbered 1,644

men. But even though the nominal strength of the Livgarde was reduced to

1,800 men in 1722, it would take until 1728 before that was achieved.

|

|

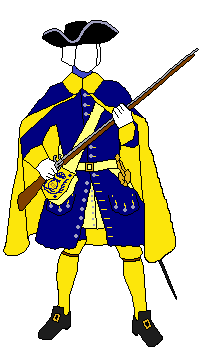

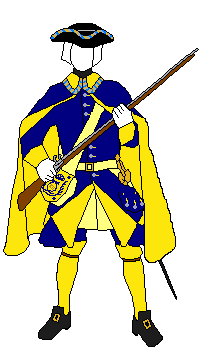

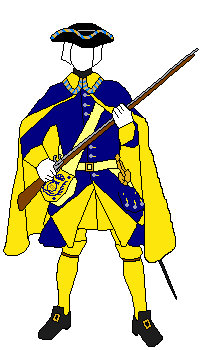

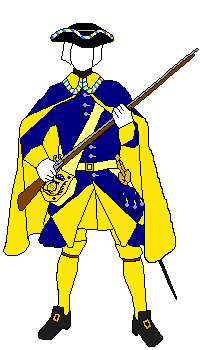

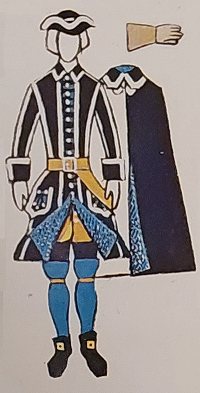

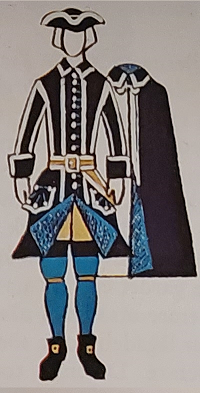

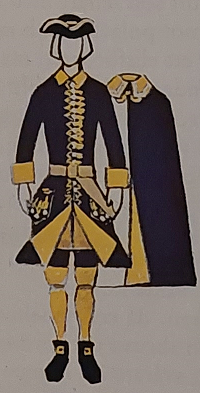

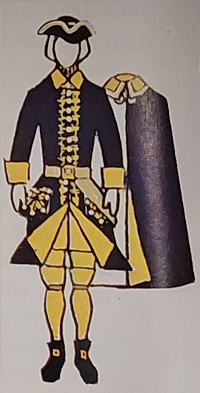

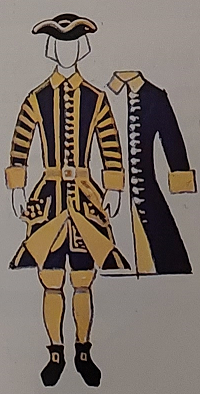

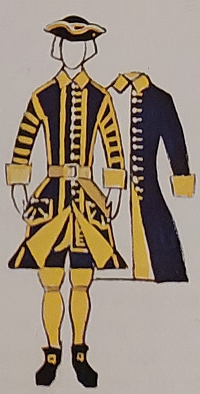

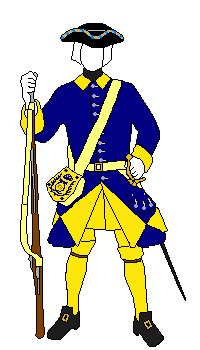

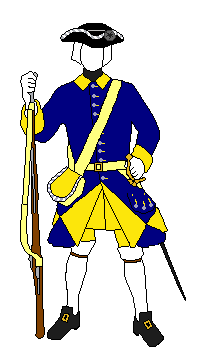

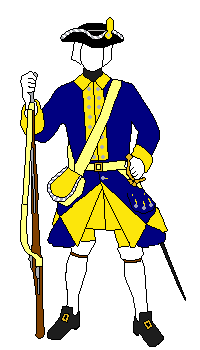

The Carolean Uniforms of the Livgarde

|

1695-1704 |

1704-1707 |

1707-1709 |

1710-1718 |

|

Colour of vest unknown. |

Vest unknown. Lace on the hat and the cloak's collar

is my interpretation of the sources' "gold, silver in silk". The other

changes

may have occurred when the

next uniform was issued in 1707 or perhaps even later. |

|

Hat lace is not mentioned and the cloak's collar is only

mentioned to have had "silk lace". I have guessed that the gold and

silver were replaced with yellow and white thread for economical

reasons. |

When

the Livgarde marched to war in April 1700 they wore uniforms that had been

issued in 1695. Although Charles XII had decreed a new uniform for his Guard

in 1699 it would not be until 1704 before the first

model 1699 uniforms were issued to the Livgarde. Then at last could the

3-männing soldiers, who had been added to the Guard in 1703, receive new

proper Livgarde uniforms instead of the red Saxon coats (captured in the

battle of Kliszow) which they had been forced to wear because of a shortage

of uniforms. As a part of the preparations for

the Russian campaign a second set of model 1699 uniforms were made in Saxony and

issued in April 1707.

But when the Livgarde was to be restored after the

battle of Poltava, the War College decided for a less expensive uniform. The

model 1709 uniform was then worn by the Livgarde for the remainder of the

war. Charles XII did however decree a new uniform model in 1716, similar to

the one from 1699. But due to delays it could not be delivered to the

Livgarde in time for the Norwegian campaign in 1718. During this campaign

the Livgarde was therefore among the worst dressed units. The lucky ones had

old worn uniforms from 1713, which was the last time the regiment had been

issued new uniforms. But since then the Livgarde's strength had more than

doubled, so roughly half of the guardsmen had not received any proper

uniforms at all. As an emergency solution, the Livgarde had been given 5,000

ell of vadmal (coarse wool) at the beginning of 1718 to remedy the

worst deficiencies. This should have been enough for coats, but the soldiers

complained in September 1718 especially about insufficient shoes and

stockings.

The descriptions below of the Livgarde's uniforms during the Great Northern

War are taken from Tor Schreber von Schreeb's article "Lifgardets

beklädnad och beväpning från Christina till Carl XII" and the pictures

are from Göte Göransson and Alf Åberg's book "Karoliner".

I have in purple text supplemented with information

from Folke Wernstedt's volume IV about the history of the Livgarde. The only uniform data that I have not included are those of oboists,

provosts and drivers.

A distinguishing feature of the uniforms of the Livgarde during the reign of

Charles XII is their "gold, silver in silk lace" which appeared on the hat

and cloak collar (but not the coat collar). What colour the silk was is

unclear, but Tor Schreber von Schreeb states that the silk was yellow and

blue, or only blue, and that it was decorated with gold and silver thread (note

4 page 66). However, Göte Göransson's pictures depict them as white edged

with gold and silver. And in the 1720s the silk seems to have been white (but

by then the gold thread had disappeared from the lace and other uniform

changes had taken place). I myself have made the lace striped in

gold-silver-blue in my pictures. But the actual pattern was probably more

decorative than that.

Note also that the

Livgarde grenadiers did not wear grenadier caps, they only had ordinary

tricornes

|

Livgarde Uniforms in

1695

(worn until January 1704)

Hat: black, decorated with hat band and

lace, for NCOs of silver. for oboists and the regimental pipers of "gold"

(i.e. gilded silver). Folke Wernstedt states the

privates had silver lace as well.

Cloak: of blue cloth, lining of yellow

baize; NCO's was decorated with "silver in gold lace" (lace of silver thread

with interwoven threads of gilded silver).

Coat: of blue cloth, lining of yellow baize

(mentioned only for corporals and privates). The NCOs' coats were adorned

with silver lace on the "sleeves and [pocket] flaps". The regimental piper's

of "gold in silver lace", the oboist's of the same lace and velvet on the

flaps, the drummers' and pipers' of "lace".

Vest: for NCOs of leather, for musicians of

blue cloth; lacing was of the same kind as on the coat.

Breeches: of blue cloth.

Stockings: some blue, some yellow.

Buttons: pewter for corporals and privates

of pewter, for others not specified. The number of

buttons on each pocket flap was in 1693: nine for officers, seven for NCOs,

five for corporals and three for privates.

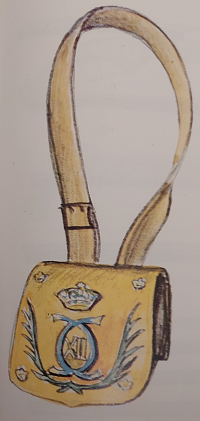

Cartridge box: in the mid-1690s had lids

covered with yellow cloth, from 1699 with yellow and blue cloth. See Göte

Göransson's interpretation of this in the picture to the right. .

Neckcloth: was of white cloth which, until

1697, was tied at the front with a blue ribbon. Possibly the colour of the

neckcloth was changed to blue at the same time.

|

Cartridge box model 1716 interpreted by Göte

Göransson |

|

Officer's Uniform

Hat: Made of camel hair felt. Hat

band and wide lace of gold (gold lace = gilded silver).

Cloak: Blue cloth with gold lace on the

collar, front and back at the slit. Gilded buckles with crowned royal

name cipher.

Coat: Of finest blue cloth, cuffs of

blue velvet, pocket flaps decorated with the same; lining of blue

"rask" (= fabric with a thin shiny surface). "Framed" (edged) with

narrow gold lace and otherwise richly decorated with wide lace and

buttonhole lace in gold. "Gold thread buttons", after 1709 possibly

gilded brass buttons.

Vest (Camisole): Of cloth like the coat

and decorated in the same manners.

Breeches: Blue cloth.

Stockings: Made of blue yarn. Gilded

buckles on the knee straps.

Gloves Reindeer skin. the collars

decorated with the gold lace. The regimental officers probably also had

gold fringes.

Waist belt: Covered with gold lace,

lined with blue cloth. Buckle gilded.

Sword tassel: Made of gold. |

|

|

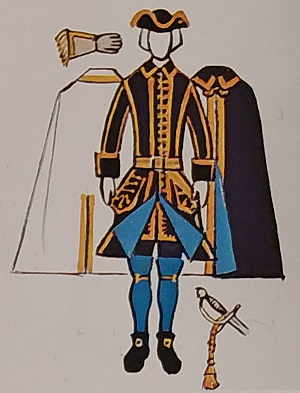

NCO Uniforms (m/1699 to m/1716)

(Göte Göransson has incorrectly

depicted officers and NCOs with lining and stockings in a lighter shade

of blue)

|

| |

m/1699

(issued in January 1704 and April 1707) |

m/1709

(issued until October 1713) |

m/1716

(was not issued in time for the Norwegian campaign in 1718) |

|

Hat: |

Lace and hat band of silver. Silver plated button. |

Silver lace, one inch wide. Hat band of white thread. |

"With silver lace" |

|

Cloak: |

Blue cloth with fin yellow baize on the collar and

lesser baize for lining. Decorated with gold, silver in silk lace (8 ell)

on the front and and back on the slit as well as the collar. Silver

plated buckles with crowned royal name cipher. |

Blue cloth lined with blue "friserad" (= surface

made uneven) baize. One inch wide silver lace on the collar. "1 pair

of silver plated brass cloak buckles, 1 pair of small plain ones on the

back of the skirt". |

Blue cloth lined with fine blue "friserad" (= surface made

uneven) baize, decorated with

silver lace. "Silver plated brass buckles, large and small, with

Carolus". |

|

Coat: |

Blue of fine cloth, 5 ½ ell "of which is also taken for

collar and cuffs. Lined with blue "rask" (= fabric with a thin

shiny surface). Edged with 11 ¾

ell narrow lace and otherwise decorated on collar, cuffs and pocket

flaps" with 8 ¾ ell wide lace and 14

ell button hole lace, all of genuine silver. 40

large "round" (lumpy) buttons of fine English pewter. |

Blue cloth lined with blue "friserad" (= surface

made uneven) baize. Decorated with one inch wide silver lace (on the

cloak collar and coat, all together 8 ¼ ell). The button holes "edged

with blue cloth". 22 silver plated brass buttons. |

Blue cloth lined with fine blue "friserad" (= surface made

uneven) baize. Decorated with silver lace (on the cloak and coat, all

together 14 ell) Button hole lace of blue silk. 26 large "double silver

plated brass buttons and 6 smaller ones on the sleeves. |

|

Vest (Camisole): |

Made of buckskin (4 hides), lined with yellow "dwelck".

Edges (8 ell) and wide lace (5 ⅞ ell) of silver.

5 ½ dozen smaller pewter buttons. |

"Camisole of buckskin with yellow "lärft"

lining and English pewter buttons". |

Made of chamois-coloured cloth, lined with fabric (above the waist "väv""

and below with chamois-coloured "lärft"). 24 smaller buttons like

the coat. |

|

Breeches: |

Blue cloth. |

Blue cloth. |

Blue cloth. |

|

Stockings: |

Blue yarn ("redgarn") |

Blue-coloured "wool knit stockings" |

Blue yarn ("redgarn") |

|

Gloves: |

Rein deer skin "with decorated small collars". |

Elk skin collars and buckskin grips. |

Elk skin collars and buckskin grips. |

|

Waist belt: |

Decorated with wide silver lace and lined with blue "lärft". Silver

plated buckle. |

Plain made of elk skin with silver plated buckles. |

Made of ox leather, decorated with 4 ½ ell silver lace and silver plated

buckle. |

|

Sword tassel: |

Of blue silk with touches of silver. |

|

|

|

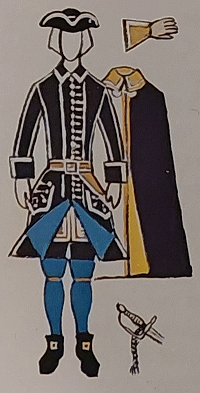

Corporals' and

Privates' Uniforms (m/1699 to m/1716)

(Göte Göransson's pictures below refer

to corporals, for privates see my pictures further up)

|

|

|

m/1699

(issued in January 1704 and April 1707) |

m/1709

(issued until October 1713) |

m/1716

(was not issued in time for the Norwegian campaign in 1718) |

|

Hat: |

Lace and hat band of gold and silver in silk. |

Decoration not mentioned.. |

Lace of silver and gold in silk. Hat band of "yellow and white

thread". |

|

Cloak: |

Blue cloth with "collar of fine [yellow] English

baize,

lined with lesser yellow baize; around the collar lace of gold and

silver in silk" (2 ell). Brass buckles with crowned royal name cipher. |

Blue cloth with a collar of "friserad" (=

surface made uneven) yellow baize and decorated with 2 ell "silk

lace". Lined with lesser yellow baize. |

Blue cloth with collar of yellow cloth, decorated with 2 ⅛ ell "lace of

silver and gold in silk". Lined with "friserad" (= surface

made uneven) yellow baize. |

|

Coat: |

Blue regular cloth "with yellow baize for

lining and fine [yellow]

baize for cuffs and collar".

Corporals: "Button holes with leaf work [likely acanthus

leaves] and double silk holes [yellow silk lace]". 31 large "flat"

pewter buttons and 6 smaller ones, the latter on the sleeves.

Privates: Single lace along the button holes (¾ lot yellow

silk instead of the corporals' 2 ½ lot). 26 large flat pewter buttons

and 6 smaller on the sleeves.

Corporals had five buttons on each pocket flap

while privates only had three. In 1707 the total amount of buttons for

privates were 19 or 20 large buttons (depending on the length of the

soldier) and 6 small buttons. |

Blue cloth with collar and cuffs of "friserad"

(= surface made uneven) yellow baize, lined with baize of lesser quality.

Along the button holes, yellow lace of camel hair yarn (2 lots). 19 "three-stamped

pewter buttons". |

Blue cloth with collar and cuffs of yellow cloth. Lined with "friserad"

(= surface made uneven) yellow baize.

24 large buttons "of three-stamped pewter and lathed with edge""

and 6 smaller ones on the sleeves. Corporals: "Double

button holes [lace] of twisted yellow camel hair yarn" with "leaf

work of yellow

silk [2 lots]".

Privates: had no lace or leaf work along the button holes. |

Cartridge box:

Lid made of yellow cloth

"with palm branches around the name [the royal cipher] sewn and a

small crown in all four corners". Se picture above.

Grenadier lids "with grenades and other

ornaments", they do not seem to have had palm branches and crowns like

the musketeers. |

|

Vest (Camisole): |

Not mentioned.

Yellow cloth in 1707. |

Yellow cloth. 18 smaller buttons like the coat. |

Yellow cloth lined with fabric ("väv"). 17 smaller buttons like

the coat. |

|

Breeches: |

Blue cloth in 1704

Yellow cloth in 1707. |

Yellow cloth. |

Yellow cloth. |

|

Stockings: |

"Yellow knitted stockings." |

Yellow. |

Yellow. |

|

Neck cloth: |

Made of black fabric. |

|

One made of black and yellow crepon", one made of whitet "lärft". |

|

Gloves: |

Elk skin collars and buckskin grips. |

Collars made of ox leather. |

Collars made of ox leather. |

|

Waist belt: |

Made of ox leather with brass buckle. |

Made of ox leather with brass buckle. |

Made of ox leather with brass buckle. |

|

Sword tassel: |

|

Leather ("smorläder"). |

Leather ("smorläder"). |

|

Drummers' and Pipers'

Uniforms (m/1699 till m/1716)

(The blue colour on the stockings on Göte

Göransson's m/1716 must be a mistake, it should be yellow)

|

|

|

m/1699

(issued in January 1704 and April 1707) |

m/1709

(issued until October 1713) |

m/1716

(was not issued in time for the Norwegian campaign in 1718) |

|

Hat: |

Lace and hat band of gold and silver in silk. |

"With sweatband and set together with a hat band twice around the

hill with white and yellow thread, and silk lace along the edge." |

Lace of "silver and gold in silk. Hat band of yellow and white thread". |

|

Piecoat: |

Piecoat of blue cloth. "The cuffs and collar of fine yellow baize and

lined with yellow lining baize. Decorated with "1 ½ dozen camel hair "litser"

(lace made of blue and yellow camel hair yarn). 18 pewter buttons. |

Piecoat of blue cloth and lined with yellow baize. 18 pewter buttons

like the coat. |

Piecoat of blue cloth and lined with "friserad" (= surface made

uneven) yellow baize. 18 pewter buttons like the coat. |

|

Coat: |

"Coats of fine blue cloth, lined on the cuffs and the "flaxor" [fabric

hanging on the shoulders] with yellow "rask" [= fabric with a

thin shiny surface] and underneath with lesser yellow baize, with [48]

gold, silver in silk buttons, decorated with gold and silver i silk

lace" (on the coat and vest, 54 ell in total). |

Coat of blue cloth with collar and cuffs covered with "friserad"

(= surface made uneven) yellow baize, lined with baize of lesser quality.

On the coat and vest, 53 ell

"lace of gold, silver in silk" in total and "2 lots yellow twisted

camel hair yarn for the button holes". 18 "three-stamped pewter buttons

with stripe". |

Coat of blue cloth with collar and cuffs of yellow cloth, lined with "friserad"

(= surface made uneven) yellow baize.. On the coat and vest, 30 ell "silver

and gold in silk lace" in total, 17 ½ ell edging lace of the

same kind and 2 lots camel hair yarn for button hole lace. 27 large and 6

smaller buttons "of three-stamped pewter and lathed with edge"" |

|

Vest (Camisole): |

Blue cloth, decorated like the coat. 36 smaller buttons like the coat. |

Blue cloth, lined under the waist with yellow baize; regular lace and

button hole lace (see the coat). 18 smaller buttons like the coat. |

Blue cloth lined under the waist with "friserad" (= surface made

uneven) yellow baize. Decorated like the coat. 23 smaller buttons like

the coat. |

|

Breeches: |

Blue cloth. |

Blue cloth. |

Blue cloth. |

|

Stockings: |

Yellow. |

Yellow. |

Yellow. |

|

Gloves: |

|

Collars of ox leather and buckskin grips. |

Collars of ox leather and buckskin grips. |

|

Waist belt: |

Decorated with 7 ½ ell gold and silver in silk lace.

Drum strap decorated with wider lace of the same (5 ¼ ell). |

Made of ox leather with brass buckle. Drum

strap of ox leather. |

Made of ox leather with brass buckle. |

|

Hair pouch: |

|

Made of black "dwelck" with lace. |

|

|

Liberty Age Uniforms |

|

m/1716

(issued at the turn of the year 1718-19) |

m/1724-1728

(issued in 1729) |

"m/1750s"

(was in use no later than 1759) |

Charles XII's m/1716 uniforms (as described in the tables above) were

finally completed and sent from Stockholm to the main army in two batches in

early November and early December 1718. However, by then the king was dead

and the campaign was over. They thus became the Livgarde's first uniform

during the new era that began in 1719. From 1724, however, several changes

took place in the Livgarde's uniform regulation. The most noticeable thing

was that the stockings now became white and that the hat brim was changed so

that the gold thread disappeared and the silk in it became white (although,

the silk may have been white all along and not blue as in my pictures above).

In addition, a black cockade was added to the hat. The cartridge box was to

be decorated with silver and white silk lace on the lid, which continued to

be of yellow cloth. I have no information about any additional decorations

but probably the lid was also adorned with the royal monogram as in Charles

XII's time. The new uniform was issued in 1729.

The non-commissioned officer uniform also changed greatly with the m/1724.

The former all-blue uniform now received pale yellow (chamois) facings,

waistcoats and trousers and, like the privates, white stockings. When the

uniform regulation was changed again in 1728, another innovation was made to

the non-commissioned officers' uniform (and the drummer's uniform). They

were to have lapels on the coat, which at this time was a common feature on

European uniforms. In Sweden, on the other hand, it was unusual and became a

distinctive feature of the Livgarde's officers and NCOs. It was only during

the 1750s that the privates also received lapels.

|

|

m/1724,

m/1726 and

m/1728

(information taken from Lars

Ericsson's article in Meddelanden från Armémuseum 45-46) |

|

NCOs |

Privates |

Drummers |

|

Hat: |

Two finger wide silver lace, one silver-plated brass

button for attachment and a cockade of double black taffeta with

sewn-on brass thread.

Silver lace and cockade as well as a black horse hair button. |

Regular black hat with white lace with silver and round

pewter button. Cockade of black taffeta and sweatband.

Silver in silk lace |

|

|

Cloak, piecoat: |

|

Cloak with silver in silk lace on the

collar and large white metal buckles and a pair of smaller brass buckles. |

Piecoat of blue cloth lined with yellow "friserad"

(= surface made uneven) baize. |

|

Coat: |

Blue with chamois collar and cuffs.

Blue lined with chamois "friserad" (= surface made uneven) baize, .chamois

cuffs and lapels and) and white buttons. |

Blue regular cloth lined with yellow "friserad" (=

surface made uneven) baize both in the sleeves and under the waist. |

Blue regular cloth with yellow collar and cuffs.

Lace with silver edged silk (it is not clear if it is for the hat or the

coat). |

|

Vest (Camisole): |

Chamois cloth underlined with "friserad" (=

surface made uneven) baize.

Chamois cloth lined with "friserad" (= surface made uneven) baize

and fabric ("väv"). |

Yellow cloth lined with fabric ("väv"). |

Yellow regular cloth lined with fabric ("väv"). |

|

Breeches: |

Chamois cloth lined with fabric ("väv").

Chamois cloth lined with fabric ("väv"). and pewter button. |

Yellow cloth lined with fabric ("väv"). |

Blue lined with fabric ("väv"). |

|

Stockings: |

White knitted yarn ("redgarn") stockings.

White yarn ("redgarn") stockings. |

White wool stockings. |

|

|

Gloves: |

Large pointed elk skin collars with reindeer skin grips. |

Regular gloves.

Two pair of grips made buck leather and reindeer leather respectively. |

|

Exactly when

lapels were introduced on the privates' uniforms is unclear. But the War

College noted in 1759 "that some time ago, the Royal Livgarde on the

coats used so-called lapels on the chest", which contradicted the

Parliament's ban on "all kinds of excesses and haughtiness occurring in

the army" and the King had also forbidden the Livgarde officers from

using lapels the year before. Despite this, the War College suggested that

all personnel should have lapels so that the Livgarde would distinguish

itself from the other regiments.

|

Hats also changed during the

1750s. The corporals received in 1751 silver lace on their hats just like

the non-commissioned officers. Also, both corporals and privates would have

"tassels" on their hats, which were introduced on NCOs' hats only in 1773. I

have no further description of what the tassels looked like. However, there

are two contemporary depictions of the m/1765 uniform that have different

types of tassels and they may be clues to what its predecessors looked like.

A more discreet type of tassel (in silver and/or white silk?) appears in

Jacob Gillberg's model drawings below, while an unknown artist in the

picture to the right has depicted the Livgarde with a long yellow pompom.

It was also noted in 1759 that the Livgarde's hats differed from the "indelta"

regiments by having "a pointed and shallow hill".

Close-up of the hat, from Jacob Gillberg's drawing of the Livgarde's

m/1765-uniform. |

Livgarde m/1765 uniform by unknown artist. |

After the

Pomeranian War, a completely new uniform regulation for the Swedish army was

introduced in 1765. The cut of the coat changed and black gaiters to cover

the stockings became standard. For the Livgarde, the button colour was also

changed from pewter to brass. However, the black gaiters were not popular

with the regimental commander who in 1772 complained that the Livgarde was

expected to wear white gaiters. He got his way, which means that the image

above on the right may give a better picture of what the Livgarde's m/1765

uniform actually looked like than Jacob Gillberg's model drawings below. In

any case, it was replaced in 1780-1781 by the Gustavian uniform (m/1779).

NCO, private and drummer with uniform m/1765 (drawn

by Jacob

Gillberg).

|

|

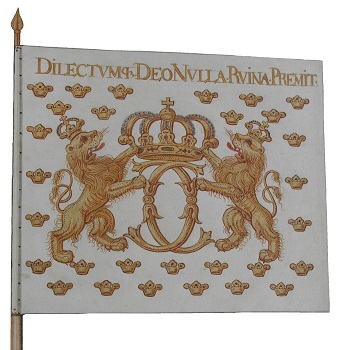

Livgarde Colours during

the 18th Century

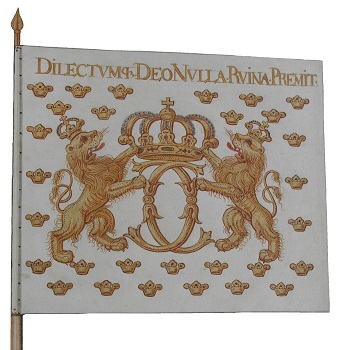

Reconstruction of m/1686 colonel's colour

(no model drawing is preserved and the motto is likely incorrect) |

Olof Hoffman's model drawing of m/1686 company colour |

According to

the regulation from 1686, the Livgarde's company colours were to look like

the picture above to the right (Olof Hoffman's model drawing). The motif consists of the

king's crowned mirrored monogram carried by two crowned lions in a white

field strewn with crowns. At the top was a motto written in Latin. The

colonel's colour was the same except that the royal monogram in the middle

was replaced by Sweden's greater coat of arms. The intent was probably that

each individual colour would have its own motto at the top, but in the set

produced in 1710, all company colours had the same motto as in the model drawing.

However, the fragmented colonel's colour appear to have had a separate motto.

All of the preserved colours from the 17th century did have individual mottos. The 1686

regulation probably did not result in any changes in the appearance of the

Livgarde colours.

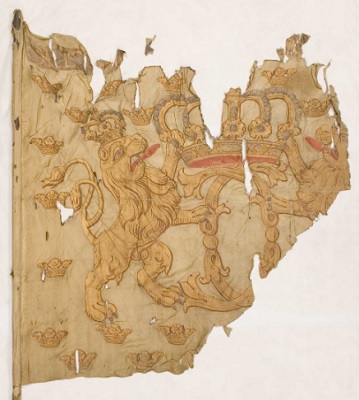

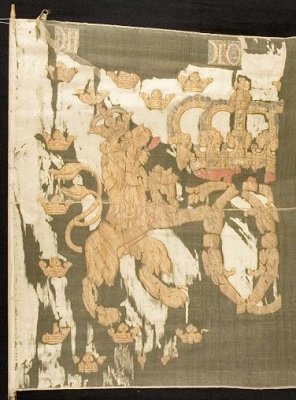

The first

m/1686 set of twelve colours was issued in 1690 and the old colours were

then donated to the regimental commander Bernhard von Liewen. But in

September 1700 the Livgarde was reorganised from twelve to eighteen

companies and the new companies needed their own colours. Charles XII

therefore asked von Liewen to return the six older colours that were in the

best condition. These older colours were likely not delivered to the

Livgarde in time for the Battle of Narva on 20 November, but should have

been used during the Battle of Düna on 9 July 1701. It is written in Captain

Olof Stiernhöök's diary that his company received a colour on 26 December

1700.

|

|

Company

colour from either 1680 or 1690

HINC PRÆMIA BELLI

(Hence the rewards of war)

295. Colour. Flag:

originally a height of 216 cm, present width 143 cm.; of white taffeta,

upon painted in gold, the same on both sides, Charles XI's cypher, large

double C underneath large closed crown with red lining; the cypher is

supported by two crowned lions with red tongues; on the bottom small

scattered open crowns; along the upper edge on the inner side HINC PRÆMIA

[BELLI •], on the outer [HINC] PRÆMIA

BELLI •; Attached with strongly domed, gilded nails and satin ribbon in

white and yellow, which continues tightly wound about the staff 38 cm. below,

attached with nails going in a spiral. Staff: length 265 cm.;

diameter

on the top 3

cm., below the flag 3,5 cm.; of pine, painted white.

Of the flag about half remains, relined on tulle;

painting well preserved; the flag taken from the staff, which is cut off

below;

finial is missing. Colour at the Livgarde, probably older than 1686. |

However, after a year of campaigning, the colours from the 17th century were

deemed to be worn out. In April 1701, a new set of 18 colours was therefore

ordered, painted by Olof Hoffman on canvases of "grein de Neapole croisse".

In this set, which was completed in October 1701, three colours were

decorated with grenades in the corners. These were intended for the three

grenadier companies that had been formed in September 1700, but they did not

come into use until November 1702 when the Livgarde was expanded with three

regular companies. Apparently the king had decided that grenadier companies

should not have colours. This was already the case when the colours were

completed since Charles XII wrote to the War College on 29 October 1701 and

mentioned that "in grenadier companies no colours are used", and this did

not change when three more grenadier companies were created in August 1703.

Olof Hoffman's set was lost to the Russians at Poltava and Perevolochna in

1709. Their descriptions mention that the finials were engraved and made of

gilded copper. All colours were taken to Moscow and destroyed in 1737 when

the Kremlin burned down.

In the Battle of Poltava, however, the Guard battalions did not only carry

the Livgarde colours. During the Russian campaign, men from disbanded

3-männing regiments had been used to fill vacancies in the Livgarde

companies. Their old 3-männing colours were carried alongside the 18

Livgarde colours. The exact number of 3-männing colours during this battle

is not known, but they were generally red with various central Swedish

provincial coat of arms in the upper inner corner. The only exception was

the Småland 3-männing regiment that had yellow colours (and at least two of

these had Jönköping's coat of arms in the upper inner corner).

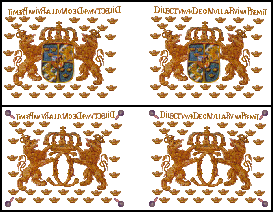

Company colour from 1710

After the disaster in Ukraine, the Livgarde was to be restored to its former

strength. But recruitment was slow and the organisation stayed for a long

time at twelve companies and it was also this number of colours that were

produced in 1709-1710 (see picture above and below). All colours had the

same motto as in the model drawing, but one deviation was that the gold text

had a silver background. The staffs were painted with dark brown paint.

However, the quality of these flags may not have been the best as the

regimental commander ordered 19 colours made of Persian damask flags in 1716

(the nineteenth colour should have been intended for the company guarding

the palace). But it doesn't seem like any new colours were delivered. In

1719 the new regimental commander complained that the colours from 1710 were

worn out, and while waiting for new colours to be delivered, he requested as

a provisional solution the colours that had been used at Ulrika Eleonora's

coronation. That did happen, but only after Fredrik I's coronation the

following year.

These twelve "coronation colours" had been ordered from France as early as

1679 and were intended for the Livgarde, but the delivery took so long that

other colours were made instead. By 1703 at the latest, however, they must

have been stored in Stockholm. Fragments of one of these banners are

preserved in the Army Museum. They were never returned when a new set of

colours was issued and were probably used as so-called "sentry colours".

This type of colour was used in daily service to avoid wear and tear on the

ordinary colours and they were usually made of cheaper materials.

|

Company

colour from 1710

DILECTUMQUE

DEO NULLA RUINA PREMIT

(The one chosen by God fear no defeat)

296 (86). Colour.

Flag: originally a height oh 178 cm., present width 136 cm.; of white

taffeta, upon painted in gold, the same on both sides. Charles XI's cypher,

large double C underneath large closed royal crown with pearls in silver and

red lining; the cypher is supported by two crowned double tailed lions with

red tongues; along the upper edge on silver base, on the inner side DIL[ECTUMQUE] DEO [NULLA RUINA PREMIT],

on the outer [DILECTUMQUE DEO NU]LLA [RUINA PRE]MIT; on the bottom

small scattered open crowns; attached with gold ribbon and gilded nails. Staff: length 350

cm.; diameter on the top 3,4 cm., below the flag 3,6 cm.; of pine, painted

dark brown;

right underneath the flag covered 18 cm. below with white taffeta, attached

with four rows of nails and gold ribbons.

The flag very broken, in older time patched; consists

only of loose pieces relined on tulle; of the inscription only two fragments

remain;

taken from the staff and again nailed to the same, but obliquely and with

longer flag than before, marks from the old nails still visible (and from

them have the measurements been taken); finial missing. Colour at the

Livgarde according to Charles XI's regulation of 17 March 1686. A deviation

from the model drawing kept in the War Archive is that the inscriptions has

been painted on a silver base and not directly on the flag. Those fragments

listed under the following number probably belonged to a colour of the same

set as this one. |

It would take

until 1726 before the Livgarde received a new set (12 regular colours and

two sentry colours). However, the appearance of these did not follow m/1686,

but had been greatly simplified. Only the king's crowned monogram remained.

The lions and the scattered crowns were gone. Instead three were closed

crowns in the corners and a company symbol in the fourth corner. The company

symbol should have been in one of the upper corners. The appearance of the

company symbols is unknown but possibly the signs of the Zodiac may have

been used as symbols. With this set, the manufacturing technique had also

changed so that the colours were henceforth embroidered and not painted. No

colours in this set are preserved. The sentry colours were quickly worn out

and three new ones were delivered in 1732-33 and three more in 1737.

The 1726 set

was replaced in 1748 with fifteen new colours (no sentry colours were

issued so probably the old regular colours were used instead). This set had

no company symbols and instead there were crowns in all the corners. In

addition, the crowns were now open and not closed. In their original state,

they had Fredrik I's mirrored monogram as a motif, but after Adolf Fredrik

became king in 1751, the colours were modified so that an A was embroidered

over the mirrored F's.

Company colour from 1748, modified in 1751 |

Company colour from 1762 or 1763 |

In 1762, six new colours were embroidered (one of which was a colonel's

colour) and in addition two sentry colours. These were supplemented in 1763

with nine more company colours. The difference to the previous set was that

the crowns in the corners were now closed again. These were then in use

until 1771-72 when a new set of fourteen colours was delivered. The only

difference to the previous set was that Adolf Fredrik's monogram was

replaced with Gustav III's. New sentry colours had to wait until 1778-79

when two such were paid for by the regimental commander himself and in 1784

when the crown paid for two sentry colours. A new set of only eight Livgarde

colours was embroidered in 1786 and it is said to have had the same

appearance as the previous set.. The last Livgarde colours of the 18th

century were issued in 1798 (1 colonel's colour, 9 company colours and 2

sentry colours) and were in use throughout the reign of Gustav IV Adolf,

with the exception of the sentry colours which were discarded after two

years).

Links to Preserved Colours

Colour sheets

|

The following images are free-to-use colour sheets for those who want to

paint miniature figure to represent the Livgarde. The company colour below is identical

with Olof Hoffman's model drawing while the two to the right are my

reconstructions of the colonel's colour and the colours intended for

the grenadier.

|

|

|

|

Other Equipment

The

Guard's drums were in

1699 blue but otherwise had the same appearance as the colours. Just like

with the colours the colonel's company was different by having the Swedish

coat of arms on their drums instead of the royal cipher. The image which is

drawn by Göte Göransson and taken from his and Alf Åberg's book "Karoliner"

shows how the colonel's company's drums looked like. The

Guard's drums were in

1699 blue but otherwise had the same appearance as the colours. Just like

with the colours the colonel's company was different by having the Swedish

coat of arms on their drums instead of the royal cipher. The image which is

drawn by Göte Göransson and taken from his and Alf Åberg's book "Karoliner"

shows how the colonel's company's drums looked like.

At the same time the Guard officers were supposed to be armed with 5 ell (=

almost 3 metre) long half-pikes with brown shafts.

The NCOs were armed with halberds with unpainted shafts.

Unfortunately I have no information about the colour of the privates' pikes.

But considering the officer and NCO pole arms as well as the fact

that the staffs for the set of colours issued in 1710 were painted dark brown, the pikes were most

likely brown, either because they were painted or because they were of

unpainted wood.

During peacetime, the musketeers of the Livgarde had been armed with

matchlock and snaplock muskets. These were exchanged for new flintlock

muskets at the outbreak of war. However, the grenadiers had previously had

flintlock muskets with bayonets. The grenadiers' weapons then proved so

effective at the landing at Humlebæk that Charles XII ordered that the

musketeers should also have this type of flintlock musket fitted with a

bayonet. At the end of October, the Livgarde therefore replaced their

muskets in Reval and were thus able to fight with bayonets in the Battle of

Narva a month later.

|

|

References

Bellander, Erik. Dräkt och uniform. Stockholm (1973).

Cederström, Rudolf. Svenska kungliga hufvudbanér. Stockholm (1900).

Ericson, Lars. Fastställda uniformsmodeller för svenska armén under 1720-talet

(article in MAM 45-46). Stockholm (1986).

Schreber von Schreeb, Tore. Lifgardets beklädnad och beväpning från Christina till Carl XII

(article in MAM 7). (1945).

Törnquist, Leif. Fanorna vid de svenska liv- och hustrupperna (article in SVSS-NS XXI). Stockholm (2006).

Wennerholm, J Bertil R. Emporterade troféer. Bohus (2000).

Wernstedt, Folke – Cson Barkman, Bertil et al. Kungl. Svea livgardes historia. Stockholm (1937-1976).

Åberg, Alf – Göransson, Göte. Karoliner. Stockholm (1976). |

|