|

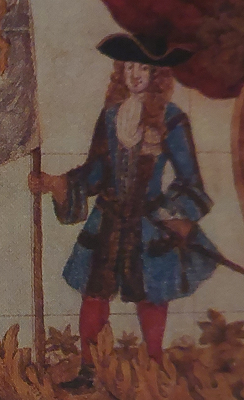

A Swedish battalion in the battle

of Düna painted by Daniel Stawert.

The uniform worn by the Swedish soldiers in the Great

Northern War is the most iconic in Swedish history and is commonly referred

to as the “Carolean Uniform”. In the popular imagination it consisted of a

tricorne hat, a knee long blue coat with yellow turnbacks, collar and small

cuffs together with yellow breeches and knee long stockings. Furthermore,

the coat would have horizontal pocket flaps with five corners and up to

seven buttons. This is the classic appearance of the Carolean uniform and

it is usually the one shown in modern illustrations.

The so called "Older Carolean

Uniform" which probably

never

saw widespread use |

However, a long held opinion in uniformology has been

that there were two distinct Carolean uniforms, separated by the year 1706,

and that only the younger uniform looked like the classic Carolean uniform.

The older uniform had a coat with no collar, large cuffs, and double

vertical pocket flaps on each side. The basis of this claim is a preserved

coat in the Swedish Army Museum which is dated to the late 17th

century. The only other preserved coats are from the Norwegian campaigns of

1716 and 1718, worn by Charles XII, his brother-in-law Frederick of Hesse

and lieutenant Drakenhielm (the latter might however be a recycled coat from

the 1690s and is conspicuously missing a collar). This view is presented as

a fact in Erik Bellander’s book “Dräkt och uniform” from 1973, which

is the major work of reference for the evolution of Swedish uniforms. But

since then more research has been done on this topic, casting doubts on the

theory of an older and a younger Carolean uniform.

Nyland drummers from 1696

who neither wear the "Older"

or the "Younger" Carolean

uniform. Contrary to the

picture, Swedish drums

usually had the same motif as

the colours. |

The most extensive research of Carolean uniforms has been

done by Lars-Eric Höglund and unlike the more general approach of Bellander

his work covers each individual regiment in the army. He has gradually

abandoned the traditional theory of the so called “Older Carolean Uniform”

being in use until 1706. The first version of his uniform book (in Swedish)

was published in 1995, with an English translation the following year. In

that book he argued that the older uniform must have been abandoned already

in the early 1690s because of all the modern features in uniforms from that

time. To cover the resulting time gap he proposed to introduce the concept

of a third Carolean uniform type (the intermediate Carolean uniform) which

according to him evolved into the younger uniform which he still dated to

1706.

However, Höglund’s view had changed even further when he

later began to publish uniform books covering Sweden’s opponents. These

consisted of two volumes in Swedish from 2003-04 which were then published

in a combined volume when it was translated to English in 2006. In the

preface to the first of the Swedish volumes, Höglund noted that an old

illustration from 1696 contained a picture of drummers from Nyland regiment

who clearly were not wearing the uniform issued to them in 1696. Hence it

had to be the one which had been issued to them in 1688. But the uniform did

not look like the so called Older Carolean Uniform, instead it looked like

the uniforms worn in the Scanian War 1675-79. Höglund’s conclusion was that

the preserved coat in the Army Museum most likely was a rejected prototype

and that the Swedish army continued to use the Scanian War type uniform

until it was replaced by the classic Carolean Uniform in the 1690s.

The Coat

Before the Swedish army adopted the Carolean Uniform they

wore the uniform used during the Scanian War 1675-79. Its main component was

the “justaucorps”, a knee-long coat of French origin which spread to all of

Western Europe during the latter half of the 17th century and would then be

the dominant fashion for well over a century. It came to Sweden c. 1670 and

replaced the older jackets, which originally had ended at the waist although

they too had gotten quite long at the time the justaucorps arrived. The

Carolean coat would evolve from this early justaucorps, with most of the

changes intended to make it more suitable for campaigns rather than to

imitate civilian fashion.

The main differences between the Scanian War coat and the

classic Carolean coat were the former’s larger cuffs, no collar, no

turnbacks and rectangular pocket flaps. The pocket flaps were however in

both cases horizontal so in that regard nothing changed, if indeed the

preserved Army Museum uniform was just a rejected prototype. The Scanian

War coat also had “edges” (lace) in the facing colour. The row of buttons on

the front covered the entire length of the coat until 1706 when they were

supposed to end at the waist. But even in the 1670s there were no

buttonholes below the waist so those buttons were just decorations.

These changes may however have been implemented gradually

and frequent regimental variation makes it even more difficult to point to a

certain date as the “birth” of the Carolean Uniform. The Guard had for

example collars already in the 1670s. The traditional date of 1687 is

nevertheless still useful since the most visually striking change was

implemented that year. On 29 May 1687 Charles XI ordered that all infantry

colonels should be sent letters with blue cloth samples, declaring that

their regiments henceforth should dress their regiments in coats with that

colour (and in most cases this also meant yellow facings).

The Scanian War uniforms had come in all kinds of colour

combinations. Rather than having a national colour common to all regiments,

Sweden had decided in a regulation from 1675 to give each regiment a

distinct colour combination, often inspired by their provincial coat of

arms. This regulation was still in use immediately after the war when new

uniforms were issued to all regiments. Since the uniforms of provincial

regiments saw very little wear and tear during peace time, this set of

uniforms would be in use for a whole decade. It was when these post-war

uniforms were due to be replaced that Charles XI ordered the change to blue

coats in 1687.

A record from 1683 show that the contemporary uniforms

still were of the Scanian War type. The coat was supposed to consist of 4

ells cloth (with a width of 2.25 ells) in the regimental colour and an

additional 0.5 ell cloth to cuffs and edges. A Swedish ell was 0.593804

metre long.

The first generation of Carolean uniforms (issued

1688-1694) had the same amount of cloth as the earlier uniforms but less of

it seem to have been allocated to facings, which is down to about a 0.25 of

an ell. This reduction might have been caused by the disappearance of

decorated “edges” on the uniforms. Collars were however planned for

Björneborg’s uniforms in the early 1680s and they were included in the coats

issued to the Dal-regiment in 1690 and for Nyland regiment in 1696 so it is

thus plausible that the “edges” were directly replaced by collars when the

new Carolean uniforms were issued. Although when Jönköping regiment was

issued new uniforms in 1692 only the corporals were given collars. In any

case, a document from the year 1700 clearly states that all infantry coats

were to have collars

Another cause for the reduction of cloth allocated for

facings is likely the introduction of the most distinctively Swedish feature

of the Carolean uniform, namely the small square size cuffs. Civilian and

international fashion dictated very large cuffs, but these were highly

impractical when soldiers handled their weapons, so Charles XI insisted that

his army should have small cuffs. While the privates’ uniforms generally

conformed to the King’s demand, the officers proved more reluctant.

Officers’ uniforms were not issued by the Crown so they had to acquire them

with their own money and many bought coats with cuffs of a more fashionable

size. Several illustrations from this time also depict officers with much

larger cuffs than those worn by the men they commanded. Charles XI, however,

did not look kindly to this and complained to the colonel if he saw large

officer cuffs when he mustered his troops.

The Guard 1693 (note the large

cuffs on the officers)

Despite the officers’ reluctance, the general trend

appears to have been that the size of cuffs shrank in size over time. Battle

paintings illustrating the Scanian War usually do not depict the very big

cuffs found in the original French fashion but cuffs of a more moderate

size. If we assume that the length of the cloth allocated to facings equals

the length of the cuffs, then the Dal-regiment was issued 22.26 cm (3/8 of

an ell) long cuffs in 1690. This was however most likely unusually large

cuffs while Närke-Värmland’s 14.85 cm (1/4 of an ell) was probably standard

at this time. The latter size is also repeated for Jämtland regiment in

1710. But Södermanland was issued 11 cm (1.5/8 of an ell) long cuffs in

1702. And Kronoberg was issued 7.4 cm (1/8 of an ell) long cuffs in 1718

which is also the same size as the cuffs on Charles XII’s preserved uniform

from the same year. The uniform lieutenant Drakenhielm wore when he died in

1718 have however 12-13 cm long cuffs, though as previously stated it might

have been a recycled coat from the 1690s.

Other than size, Swedish cuffs also differed from the

more fashionable international cuffs in the way which they were fastened on

the sleeves. They were not fastened with buttons and instead sewn on to the

sleeves. The backside of the Swedish cuff may have had a slit which enabled

the soldier to reach three small buttons at the end of each sleeve. This was

at least the case for the Guard and the three preserved Carolean uniforms

David von Kraffts painting from 1706.

The text in the corner states: "King Carl the

XII such dressed as when he went on his

campaign Anno 1700". |

Another distinctive Swedish feature on the coat was the

early adoption of turnbacks. Exactly when this happened is however not

known. The cavalry is depicted by the painter Johann Philipp Lemke

(1631-1711) to occasionally wear turnbacks during the Scanian War, although

those paintings are probably anachronistic. A picture from 1696 does however

show cavalrymen from Nyland Regiment with turnbacks. Later some cavalrymen, but none of the

infantry, are shown with turnbacks in illustrations by Daniel Stawert (died

c. 1711) and Johan Lithén (1663-1725) of the battles of Narva and Düna,

which were made not long after the events occurred. Hooks used for turnbacks

are also noticeably absent in the detailed specifications of the materiel

used for uniforms to Södermanland infantry regiment, Swedish Life Regiment

on Foot and the Pomeranian Cavalry Regiment in 1700-02. But the cavalrymen at

Södra Skånska were instructed to turn back their coats in 1702. The evidence would

thus suggest that Swedish soldiers in general did not wear turnbacks in the

early years of the war, at least not the infantry. Erik Bellander has

however suggested that there likely was a transition period during which the

soldiers on occasion had their coats turned back for practical reasons (such

as riding, marching and fighting) but otherwise wore them as fashion

dictated until turnbacks became a permanent feature of the uniform. A

possible date for the latter could be 1706 when Charles XII ordered that

there should be no buttons on the coat below the waist. Since these buttons

had been mere decorations from the very beginning, the permanent adoption of

turnbacks would have made them completely redundant. Also noteworthy is that

a famous painting of Charles XII was made in 1706 with the usual turnbacks

on his coat. The text on that painting explicitly states that it shows how

Charles XII was dressed when he was on campaign in 1700.

The year 1706 has traditionally been the date for the

birth of the “Younger Carolean Uniform”. This is because of the above

mentioned letter which not only ordered the reduction of the buttons, but

also declared that the uniforms should be wider. The latter meant increasing

the amount of cloth from the usual 4 to 4.5 ells to as much as 5.5 ells per

coat. The extra amount of cloth would have been used to increase the number

of folds on the lower part of the coat, thus enabling the “bell shape” of a

true justaucorps. 5.5 ells was the amount of cloth an NCO of the Guard was

required to have already in 1699. Officers and NCOs generally had coats that

were not just of better quality but also consisted of more cloth. However,

as far as the privates are concerned there is nothing that suggests that the

increase to 5.5 ells cloth was a permanent one. In all likelihood Charles

XII just took advantage of the fact that his new luxurious uniforms in

1706-07 were paid for by generous contributions from the Saxon tax payers.

When the Swedish army had to be restored after Poltava the new uniforms had

the same dimensions as before 1706. The only lasting change was the buttons.

Swedish troops in the battle of Gadebusch painted by Magnus Rommel

Buttons

Throughout this time period the number of buttons on the

coat varied, although the general trend was that they decreased. The

Scanian War coat generally had just 30-32 buttons, but the Guard decorated

their coats with as many as 48 buttons. From 1680 to 1699 it was regulated

that Guard coats should have just 36 buttons and this was also the number

that was used when the first Carolean uniforms were issued to the provincial

regiments c. 1690. At least two regiments decided however that 36 buttons

were not enough. Närke-Värmland’s coats (worn until 1705) had 42 buttons and

the Dal-regiment’s coats (worn until 1701) had 48 buttons.

From 1699 Guard coats were regulated to have just 26

large buttons and six small ones (the latter were for the sleeves). The

regular regiments may have suffered greater reductions as three of them were

issued coats with 30 buttons in 1702. Furthermore, a cavalry coat for the

Livregemente was to have 24 buttons in 1706 and about the same time an

infantry regiment (de la Gardie’s) was to have just 21 buttons.

After Poltava, even the restored Guard was issued coats

with just 19 buttons, the same as the restored Adelsfana regiment. The Guard

would later have their button count increased to 24 large buttons and six

small ones when Charles XII returned to Sweden (regulation of 1716). And at

least two regiments were issued coats with 21 buttons (Jämtland in 1710 and

Västgöta 5-männings in 1712). But Kronoberg regiment was issued coats with

just 18 buttons in 1714.

The reason for the reduction of buttons could be

economical, especially after 1709, but the decision in 1706 to not have

buttons below the waist was probably due to fashion (permanent turnbacks?)

and must account for a very large share of the reduction. A specification of

where the buttons were located can be found for the Guard in 1707:

|

11-12

1

3

3 |

on the front, depending on the length of the soldier

on each side (of the waist)

on each pocket flap (5 for corporals)

(small) at the end of each sleeve |

All in all this meant 19 or 20 large buttons and six

small buttons. This was less than the 1699 regulation required, but that is

likely caused by the 1706 decision to eliminate buttons below the waist.

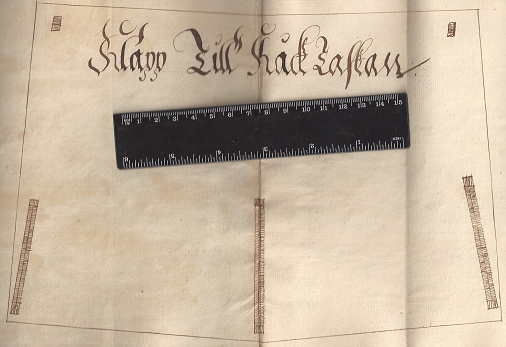

An instruction from 1709 that shows how the Adelsfana's

pocket flaps with three buttons should look like. (A ruler has

been added to the photo which shows that thepocket flaps

should be 24 cm wide at the top and 18 cm high in the middle) |

Note that this specification makes no mention of buttons

for shoulder straps. The three preserved Carolean coats did not have

shoulder straps either. The Adelsfana uniform of 1709 did however have one

button allocated for a shoulder strap intended for the carbine belt, so this

might have been standard for cavalry uniforms but not for the infantry.

The fact that guardsmen should only have three buttons on

each pocket flap is also noteworthy because modern illustrations usually

depict Carolean pocket flaps with seven buttons. The fact is that there is

no reference for private soldiers to have been issued anything but three

buttons on their pocket flaps during the Great Northern War. The

Livregemente (in 1700) and the Adelsfana (in 1709) are also reported to have

had just three buttons. Regulations from 1727 and 1729 state however that

cavalrymen and dragoons should have five buttons on their pocket flap, but

that were in the post-war era.

The reason for the seven buttons misconception is that

all three preserved Carolean coats have that number of buttons on their

pocket flaps. But those coats belonged to royalties and officers and are not

representative for private soldiers. The number of buttons on the pocket

flaps was clearly an indication of rank and an illustration from 1693 show

how the various ranks of the Guard were distinguished at that time:

Charles XII's coat from 1718

One pocket flap is missing a

button |

9 buttons for officers

7 buttons for NCOs and private drabants

5 buttons for corporals

3 buttons for private guardsmen |

For at least the latter two categories this arrangement

was still in effect for the Guard in 1707. And we also have examples from

other regiments where the total number of buttons for the coat differed

between ranks. Närke-Värmland’s coats from the 1690s had 42 buttons for

privates and 54 for corporals. The Dal-regiment had at the same time 48

buttons for privates and an astonishing 96 buttons for NCOs and officers!

Portraits of officers who fought in the Great Northern

War show us that they could have anything from three to twelve buttons on

their pocket flaps. Apparently the regimental variation was great and we

cannot assume that the seven button pocket flap worn by Charles XII, his

brother-in-law and lieutenant Drakenhielm represented a widespread standard

for showing an officer’s rank.

Besides counting buttons, the illustrations from 1693 are

also interesting because they depict the classic Carolean Uniforms’s

horizontal pocket flaps with five corners, thus implying that they were

included from the very beginning.

Drabants with hats and Uppland

grenadier with karpus in the

battle of Düna painted by Johan Henrik Schildt

Headgear

|

Charles XII's hat from 1718. |

The Swedish army had two basic types of headgear, either

the hat made of felt or the “karpus” which was a cap with flaps and usually

made of cloth. Both types had coexisted in the Swedish army even before the

introduction of the Carolean uniform and would continue to do so throughout

the Great Northern War. The former was at first a wide brimmed hat which

then evolved into a tricorne. Exactly when this transition occurred is not

known since written sources do not distinguish between these two hats. The

transition is also obscured by the fact that the karpus was the most widely

used headgear when the hat fashion changed.

The karpus became much more common after the end of the

Scanian War, and when the Swedish provincial regiments received their first

Carolean uniforms in the late 1680s and early 1690s they appear to have been

exclusively issued the karpus. The great advantage with this type of

headgear was that it was well suited for the cold Swedish climate, with the

men being able to pull down the flaps to protect their ears. The downsides

were that it was more expensive and that it likely was viewed by many as a

form of peasant clothing unbecoming of soldiers. The latter point is

strongly implied by the fact that officers continued to wear the more

fashionable hats even when their privates were issued karpus. Already in

the late 1690s a move back to hats is noticeable among the cavalry

regiments, which were soon to be followed by the infantry in the early years

of the war. Enlisted regiments also seem to have had little interest in the

karpus throughout this time period.

Officer from Tavastehus Regiment

1696 who might be wearing a tricorne.

His cuffs are large though. |

In the early battles of the Great Northern War all

Swedish infantry regiments wore karpus, with the only exceptions being the

Guard and newly raised 3-männing regiments. But when the Russian campaign

started in 1707 all Swedish regiments in the main army wore hats, with

Västerbotten regiment being the only exception. The karpus did continue to

be issued to regiments in the latter half of the war, but it was by then a

much rarer sight. The distribution of the two types of headgear also had a

clear geographical pattern in that it was the northern regiments who were

the last to abandon the karpus.

The earliest illustration of what

looks to be a Swedish soldier wearing a tricorne hat is from 1696 and it

depicts an officer of Tavastehus regiment. Later two separate sources, a

painting of a member of the Princess’ drabant corps in 1704 and a manual

from 1705 with drawings of artillerymen, clearly show them wearing

tricornes. But paintings of the early battles of Narva and Düna by Daniel

Stawert suggest that the hats were still in a transition phase then with

many different styles of hats in use. Some have hats with three sides folded

up, but usually there were just two sides folded up although this was done

in many different variants. Many hats had for example two sides folded up so

that it looked like a tricorne from the front but like a wide brimmed hats

from the back. After Düna there is no contemporary battle painting showing

these details until Magnus Rommel (1678-1735) illustrated the battle of

Gadebusch, and he depicts the entire army wearing tricornes.

There was also a third type of

headgear in the Swedish army, namely the grenadier cap. That was however a

very rare sight since Swedish grenadiers generally did not wear those. Of

well over a hundred infantry units only thirteen are known to at some

point in time have worn grenadier caps during the Great Northern War.

There actually was a proposition put

forward in 1700 to equip the grenadiers with caps just like the Dutch and

German armies did, but Charles XII rejected it.

Obviously there was no ban against grenadier caps in the Swedish army, but

any colonel who wanted to equip his soldiers with those had to pay for them

with his own money.

The first reference of Swedish grenadier caps is from 1691 when the

Dal-regiment purchased a set. But as previously mentioned the Dal-regiment

distinguished itself during the 1690s by having very extravagant uniforms.

Nevertheless, when the regiment increased its number of grenadiers by 50 %

in 1693 the new grenadiers had to wear the karpus since no additional

grenadier caps were purchased.

The correct appearance of

the

grenadier cap from De la

Gardie's Regiment. |

It is not known what the Dal-regiment’s grenadier caps

looked like, but we have descriptions and preserved caps from other

regiments and from these samples it is clear that the variation was great.

There were for example caps completely made of cloth as well as those with a

bear skin brim or a brass plate. Since there was no regulation the design

was completely up to personal taste of each colonel.

The most well-known preserved Swedish grenadier cap

belonged to De la Gardie’s regiment and it was taken by the Russians when

Narva fell to them in 1704. This cap is blue with red facings, just like the

uniform of the Narva garrison regiment. Unfortunately misconceptions caused

by black and white photos have led to more than one illustration with

incorrect colourations. One of these can be found in a colour plate in the

Osprey campaign series book on the battle of Poltava where a large part of

the front is incorrectly blue. The Osprey book has also incorrectly depicted

the grenadier as wearing a blue coat with yellow facings instead of the red

facings found on the cap. This particular mistake has since then

regrettably been copied by several other illustrators and painters.

Hair

Swedish soldiers were since the 1680s required to wear

their hair in a black pouch. The only exception being the artillery which

could let their hair hang free. This regulation would remain in place until

the 1720s when it was replaced by the Prussian inspired soldier's queue, or

pigtail as it is also called. This change in hair fashion would be the only

distinctive feature that separated the appearance of Swedish soldiers in the

Great Northern War from those in the Seven Years War four decades later.

Paintings do show however that despite of this soldiers did not always have

a hair pouch. Furthermore, two officers wearing a queue can be found as

early as in the illustration of the battle of Gadebusch made by Magnus

Rommel.

Neckcloth

The neckcloth was originally tied at the front with a

separate and different coloured ribbon to form a cravat. But in the late

1690s this changes into the Great Northern War practice of tying the

neckcloth behind the neck. The ribbon used to tie the neckcloth disappears

at the same time and interestingly the Guard was in 1697 permitted to use

the money previously spent on those ribbons for acquiring hat lace instead.

The colour of Swedish army neckcloths was originally

black but Charles XI did not like that colour and the first Carolean

uniforms saw much diversity in colour choices between the regiments. At the

end of the 1690s however, the black colour came back and together with white

they were to be the dominant neckcloth colours in the army during the Great

Northern War, even though other colours still occurred.

An overview of Swedish neckcloth colours for each

regiment can be found in this page.

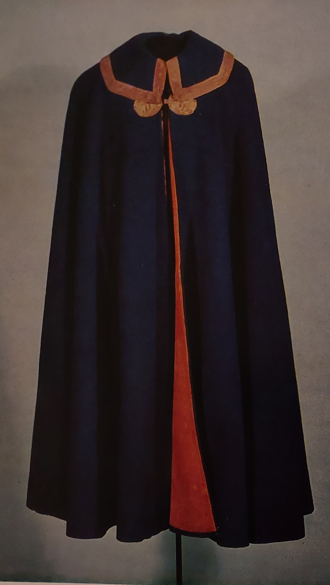

Piecoat and Cloak

An officer

cloak with gold

lace from the reign of

Charles XI. |

When the first Carolean uniforms were issued around the

year 1690 an overcoat called piecoat was included. This item was usually

made of grey “vadmal” (coarse wool) with blue facings and was used

both to keep the soldier warm and to protect the regular coat from bad

weather. But Charles XI decided already c. 1692 that the soldiers should be

issued cloaks made of cloth (usually blue with the collar and lining in the

regimental colour). Since the cloak had the same function as the piecoat,

this had the effect that the cloak soon replaced the piecoat altogether.

Drummers would however continue to wear the piecoat throughout the period.

The piecoat made a brief comeback among privates after Poltava when almost all of the restored

infantry regiments appear to have been issued this instead of the cloak

(only Västmanland is known to have received cloaks). This measure was taken

for economic reasons and later in the war several of these regiments are

known to have had cloaks again.

While other reforms of the Swedish uniform during this

time period served the purpose to make them more suitable for military use,

the wide scale adoption of cloaks seem to have been motivated by aesthetics

rather than functionality. The colonel of Västerbotten regiment wanted in

1696 to get rid of them by stating that his soldiers had too many items of

clothes to carry on the march and that the cloak took longer time to dry

than the piecoat. He did however acknowledge that the cloak did much to

increase the stature of the soldiers while on parade, although he claimed

that this was only needed for soldiers garrisoning cities where foreigners

could see them. The king was however not convinced by this complaint and the

cloak would remain a part of the Carolean uniform.

"Släpmundering"

Another grey vadmal coat issued to the Swedish

soldiers was a part of the outfit that was called “släpmundering”, a

term that could be translated to “work-clothes”. The regular uniform was

called “livmundering” and the army took great lengths to avoid

unnecessary wear and tear to this uniform. For example, provincial soldiers

had to keep their livmundering sealed in coffins during peace time

and be subjected to regular inspections of their condition. They were only

allowed to wear the livmundering during the annual regimental drill

(not even during the monthly company drills). So when soldiers had to do

tasks that posed a risk of getting their cloths dirty or even ruined, then

they wore their släpmundering in grey vadmal instead.

Grey vadmal (= undyed coarse wool) was a much

cheaper material since it cost less than half of the blue cloth. So when the

Swedish army had to be restored after Poltava, the Defence commission

considered to issue grey vadmal coats instead of a proper “livmundering”

in order to save money. They relented however after hearing numerous

objections accusing such a move to be counterproductive because blue cloth

was more durable than vadmal, also better for preserving the men’s

health and better for their moral since it meant that their uniforms would

distinguish them from ordinary peasants.

|

Charles XII's vest

from 1718 |

Nevertheless, there are numerous examples of regiments

being issued only a släpmundering and not a livmundering

during the Great Northern War. For example the first uniforms issued to the

newly raised 3-männing infantry regiment were all in grey vadmal. The

Swedish state finances during the war were anything but good so compromises

had to be made.

Vest and Breeches

Underneath the coat a vest was worn which despite the

modern meaning of that term actually had sleeves. The vest was together with

the breeches usually made of leather. Like in other armies a transition from

leather to cloth can be noticed in the Great Northern War. The uniforms of

the 1690s had these items almost exclusively made of leather while cloth

became more common after the outbreak of the war, although leather would

remain the dominant material in the Swedish army throughout the war.

The upside with leather was that it was a much more

durable material. Cloth was on the other hand more comfortable as it unlike

leather did not take so long to dry after it had been wet.

Stockings, Shoes and Gaiters

The infantry were usually issued two pairs of knee long

stockings in the regimental colour (although each pair could have a

different colour). They were also issued a pair of “marching stockings”

which were usually grey and intended to be used while marching to save the

regular stockings from wear and tear.

|

"German shoes" m/1756 |

In a similar fashion the foot soldiers were also issued

two different pair of shoes, a pair of “Swedish shoes” and a pair of “German

shoes”. The latter came with a buckle and closely followed the civilian

fashion. The “Swedish shoes” were also called “marching shoes” and might

properly have been called boots. These were more suitable for marching,

trench work and walking in snow but were of course not as pretty as the

German styled shoes.

A feature on both types of shoes as well as the cavalry

boots was that they did not follow the shape of the foot. The right shoe and

the left shoe had the same shape and ended with a flat vertical front. This

peculiar shoe fashion existed in Sweden from the 1640s to the 1760s but it

is a common mistake among modern illustrators to depict shoes from this

period with a rounded shape.

The Swedish marching shoes were however not enough to

protect the soldiers’ legs from the elements. A precursor to the gaiters

were the so called over-stockings which were pulled over the regular

stockings. Actual gaiters are also known to have been used by several

regiments in the latter half of the Great Northern War.

Cavalry uniforms

A cavalryman with a

buff coat

and

cuirass but no cloth coat

worn over it. |

The cavalry uniforms differed more

from the infantry than the fact that they had cavalry boots instead of

shoes. They were also supposed to have a cuirass underneath their coat which

meant that it had to be wider than the infantry coat. Although, judging from

some paintings, cuirasses might also have been worn over the coat. In any

case the Swedish cuirasses retained its natural steel colour and were not

blackened for rust protection as was usually done to Swedish sword hilts

(and for Danish cuirasses).

The cuirasses were however not

popular among the men and it was very common that the men “lost” them during

campaign. For example, Södra Skånska regiment reported that they in 1703

only had 354 cuirasses left and in the following year only a handful

remained. The lost cuirasses were replaced though and offenders were

punished, at least in the main army as Charles XII apparently was adamant

that his cavalry should wear them. But elsewhere the enforcement of the

regulation seems to have been less strict. Cuirasses are completely absent

from lists of equipment in Lewenhaupt’s army. And a manufacturer of

cuirasses complained in 1711 that they had not received any commissions in

years, which strongly suggest that the restored regiments after Poltava were

not issued cuirasses. It was not until 1716 that the manufacturer received

new commissions, and this was most likely a result of Charles XII’s return

to Sweden.

Also worn underneath the coat in the early days of the

Carolean uniform was the buff coat (“kyller”) which originally had preceded

the justaucorps as the primary cavalry coat. But as an undergarment the buff

coat was soon replaced with the vest used by the infantry. When war broke

out in 1700 the Swedish cavalry wore their leather vests on campaign and

left the buff coats at home.

While 1687 is commonly referred to as the year when dark

blue became the standard Swedish coat colour, it is worth mentioning that

this at first only applied to the infantry. When the war started only six

of the 14 provincial cavalry units had dark blue coats. The largest and most prestigious, Livregementet, wore

together with Södra Skånska light blue uniforms. All Finnish units as well

as the Adelsfana and Jämtland Cavalry Company wore grey coats. And the Bohuslän Dragoon squadron wore

very distinctive green coats. However, dark blue became the standard colour

for the newly raised regiments and in the early half of the war the older

regiments switched to dark blue as well. The one exception was the Bohuslän

dragoons who successfully resisted these attempts and would remain green

throughout the 18th century.

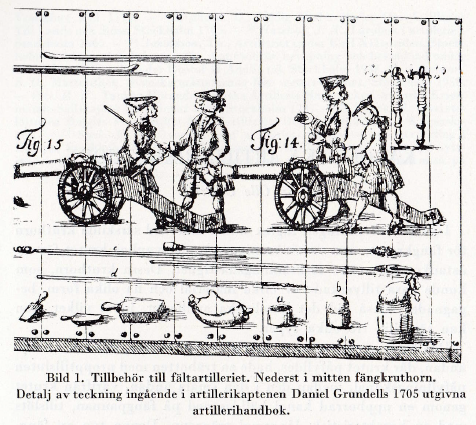

Drawing of artillerymen from 1705 by Daniel

Grundell

Artillery uniforms

The artillery was also exempted from the 1687 reform and

continued to wear grey coats with blue facings until they gradually

transitioned to all blue uniforms during the first half of the war.

They also distinguished themselves by not wearing hair

pouches or turnbacks during the Great Northern War, although they would

adopt them in the 1720s.

Officers and NCOs

As previously mentioned the number of buttons on the

pocket flaps was used to distinguish the different categories of rank in the

Swedish army. Officers and NCOs were furthermore distinguished from the men

by having all blue uniforms and not facings and stockings in the regimental

colour, although this was not the case in all regiments. Officers would have

gold lace on their hats and coats while NCOs had silver lace instead.

However, the cavalry frequently had silver hat lace for the privates (and

occasionally gold lace too) so it was not uncommon for cavalry NCOs to have

gold lace instead of silver.

Unlike the other European armies, Swedish officers did

not wear a sash. Infantry officers and drabants did however wear a gorget as

rank insignia. And just like their cavalry colleagues, infantry officers

were also supposed to have cuirasses (though if they actually did is a

completely different matter).

During the Great Northern War Swedish officers was to

have the following appearance of their gorgets and parade coat in accordance

to their rank (the latter also includes cavalry officers):

A captain's gorget from the reign of Adolf Fredrik

(1751-1771)

|

|

Gorget |

Parade Coat |

|

Colonels |

Gilded silver with the royal cypher and other decorations (lions?) in

enamel. |

Was allowed to distinguish himself from his subordinates with as much

as he could afford. |

|

Lieutenant Colonels &

Majors |

Gilded silver with the royal cypher and palm wreaths in enamel |

Wide gold lace on cuffs and pocket flaps. Buttons and buttonholes

decorated in gold. |

|

Captains |

Gilded silver with the royal cypher in blue enamel |

Narrow gold lace on cuffs and pocket flaps. Buttons and buttonholes

decorated in gold. |

|

Lieutenants &

Ensigns |

Polished silver with the royal cypher in gold |

Buttons and buttonholes decorated in gold. |

The table above describe the parade coat but the

regulation also stipulates that in addition to that company officers should

have a plain blue coat with blue cloth buttons while on guard duty or in

camp. Furthermore a third coat was to be grey with pewter buttons and used

for marching.

All this was however just regulation, reality could be

very different. Officers had to purchase their own uniforms and it was

common to save money by not fully comply with the demands of the regulation.

For example, there are over 60 preserved gorgets that were captured at

Poltava and almost half of these do not have the royal cypher. 15 gorgets

are made of copper but 11 of those do have the royal cypher.

The economic difficulties seem to have been exceptionally

harsh for the officers of Jämtland regiment who were protecting the

Norwegian border up north. In 1708 they are reported to have had half-pikes

(spontoons) and gorgets of the prescribed model, although the latter were of

brass instead of silver. Everything else though, such as clothes, cuirasses,

swords, muskets, wagons and tents were missing because of their poverty, bad

harvests and the fact that for six years they had only received half pay.

Uniform Quality

It might have been intended that privates also should

have had three different coats. Although the sources generally only speak of

two types of uniforms; the regular “livmundering” and the work

clothes called “släpmundering”, they do use the latter term to

describe two types of clothes; either an outfit of grey vadmal which

had been manufactured for the sole purpose of being used as work clothes, or

an older livmundering that had been replaced by a new one. The grey

vadmal outfit could have been used for work where there was a risk of

getting dirty while the older livmundering could have been used as an

everyday uniform. Thus a similar arrangement to that of the officers who

were supposed to have three types of coat. There is evidence to support

this theory and that is a letter from the colonel of Västerbotten regiment

who in 1699 addressed the difficulties in storing three sets of uniforms,

one of which was as old as from 1683.

But even though it might have been intended that soldiers

should have had three sets of uniforms, reality was different and Swedish

soldiers would be fortunate if they had just two sets of uniform. As

previously stated there are numerous examples of regiments who had to wear

their grey släpmundering because they had not been issued a

livmundering. There might also have been cases of regiments not being

issued any uniforms at all. The national militia regiments in the German

provinces, which were raised in 1710, have no records of uniforms and

captured militia soldiers are described in Danish sources as wearing

peasants’ clothes.

The idea of using an older livmundering as

everyday clothes was probably not realistic, because by the time a regiment

was issued new uniforms, the old uniform would have been so worn out that it

would not be in an acceptable condition. In 1693 it was decided that a

provincial regiment should receive a new uniform every seventh year. An

enlisted regiment would however need new uniforms every second year (later

every third year) since they were full time soldiers. But as always,

regulation was one thing, reality was different. When war broke out in 1700,

most of the Swedish army’s uniforms were past their expiration date. Just

look at the following sample of regiments for which the terms of the first

Carolean uniforms are known.

|

|

Post Scanian War Uniform |

First Carolean

Uniform |

Second Carolean

Uniform |

|

Dal-regiment |

1681 |

1690 |

1702? |

|

Hälsinge |

? |

1693 or 1694 |

1701 |

|

Jönköping |

1681 |

1692 |

1704? |

|

Kronoberg |

? |

1692 |

1702 |

|

Närke-Värmland |

Not earlier than 1681 |

1691 |

1704-05 |

|

Skaraborg |

1679 |

1689 |

1701 |

|

Södermanland |

? |

Not later than 1690 |

1702 |

|

Uppland |

1683 |

1691 |

1701/02 |

|

Älvsborg |

? |

1687 |

1709 |

|

Östergötland |

1681 |

1692 |

1701 |

Apart from maybe Hälsinge, no regiment in the

sample above received new uniforms within seven years. And yet the most

extreme example is not included here; Jämtland regiment was issued uniforms

in 1682/83 which were not replaced until 1709. Not even the enlisted

soldiers of the Guard got new uniforms within seven years; those that were

issued in 1695 were not replaced until 1704.

A likely reason why the regiments did not receive new

uniforms in the late 1690s is the fact that a series of bad harvests

culminated in the years 1695-97 and resulted in what is probably the worst

famine in Swedish history. It is thus understandable that the government

felt there were more important things to spend money on than to buy new

uniforms for its army.

Nevertheless, when the war started both the old and the

newly raised regiments needed uniforms and this put a great strain on the

Swedish finances. Priorities had to be made and those regiments who stayed

home in Sweden, such as Jämtland, had to wait very long for new uniforms.

Many of these did however receive new uniforms in time for the Danish

invasion of 1709. Not so fortunate was however the Skånska 3-männing cavalry

regiment which already when it was raised in 1700 received a decade old

uniforms from Södra Skånska Regiment. These were in an appalling condition

when they confronted the Danes in 1709 and they suffered wide scale

desertions, although they did receive partial replacements in time for the

battle of Helsingborg.

While the Swedish uniforms left much to desire at the

beginning of the war, things did improve somewhat. The main army that left

Saxony for Russia in 1707 was probably the finest looking Swedish army

during the entire war. And while conditions were not good during the Scanian

campaign of 1709-10, the uniforms were at least new. However, the attrition

rate was high during a campaign and the musters held in the summer after the

short Scanian campaign reveal considerable losses in material. One of the

less fortunate regiments, the 1 100 men strong Kronoberg, reported that the

following items had been lost since the last muster:

| 353 |

Blue coats |

| 175 |

Piecoats |

| 158 |

Hats |

| 179 |

Leather vests |

| 275 |

Leather breeches |

| 1 100 |

Black neckcloths |

| 1 100 |

Brass shoe buckles |

| 1 100 |

Knee straps for stockings |

It

was under dire economic conditions that Sweden had to fund replacements for

worn out uniforms for the duration of the war as well as restoring yet

another lost army in 1713. The quality of the uniforms would therefore vary

considerable from regiment to regiment depending on how long it was since

they had been issued new uniforms.

The End of the Carolean

Uniform

The Carolean time period in Swedish history ended with

the death of Charles XII in 1718. Thus ended the absolute rule by kings and

instead an era of parliamentary rule began. This revolution did however not

affect the Swedish army uniform since it would look pretty much the same for

nearly half a century afterwards. The only real changes were the hairstyle

and a more widespread use of gaiters.

|

Uniform m/1756 |

The new regime showed little interest in uniforms other

than reducing its costs. The difficult financial situation was not only

caused by the huge war debt it had inherited from Charles XII. The

territorial losses also meant that a very large share of the tax revenue in

the pre-war budget was now gone forever. This loss of tax revenue needed to

be compensated for somewhere else. But all the reforms that Charles XII had

taken in that direction to fund the war effort was rolled back by the new

regime who viewed them as evils of absolutism. So the pre-war tax system

remained in place during the entire period of parliamentary rule with a

permanent structural budget deficit as a result. Foreign subsidies and

temporary taxes had to do to solve any acute crisis, among these two

unnecessary and unsuccessful wars started by the Hat party in 1741 and 1757.

Very little money was thus spent on the military and

uniforms were replaced at longer intervals than before. In addition the

quality of the issued uniforms declined due to widespread corruption during

this time period.

A major uniform regulation was introduced in 1756

although it did not bring any real changes to the uniforms apart from

declaring that all infantry regiments henceforth should have yellow facings.

It was however much more specific than any previous regulation in describing

what the uniform should consist of and how often the items should be

replaced. The coat for example should now be replaced just every twelfth

year. But as always reality was different, the Bohuslän dragoons were still

wearing the coats they had been issued in 1748 when a muster was held in

1767.

It was the experience in Pomerania while fighting the

Prussians 1757-1762 that would bring the end of the Carolean uniform.

Officers complained that it was too difficult to distinguish the different

regiments when they all wore identical uniforms. But it must also have been

a factor that compared to the other armies fighting in that war the Swedish

uniform looked rather plain and old-fashioned. So a new uniform regulation

came into being in 1765 which not only increased the diversity of facings

colours but also changed the style of the coat so that it would resemble the

victorious Prussian army. This uniform was however still a close relative to

the Carolean uniform, though it would in its turn be replaced already in

1779 by a radically different uniform. That was the Gustavian uniform, which

was designed by the fashion interested king Gustav III in a style that was

to be unique for Sweden. But that is a different story.

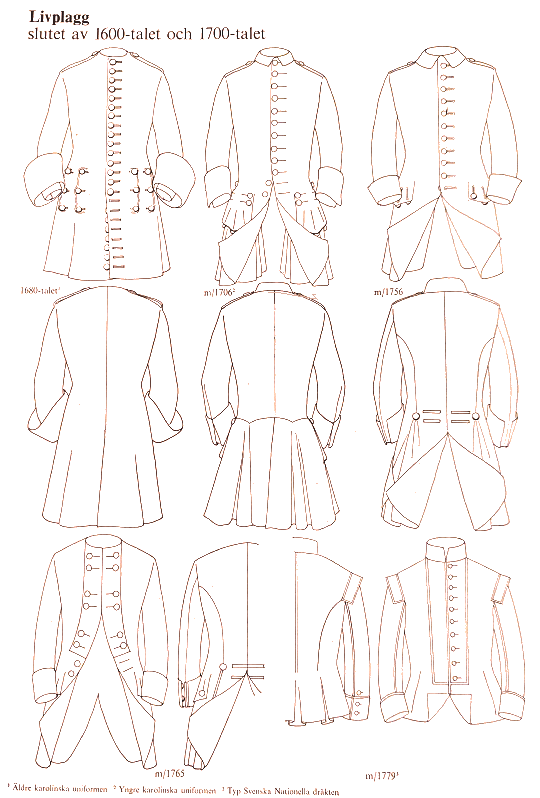

A sketch from Erik Bellander's book (page 565) which shows the various

uniform models of the 18th Century.

-

The so called Older

Carolean uniform which probably

was a prototype and not widely used.

-

The Younger

Carolean uniform, here called

m/1706 but probably looked like the first Carolean

uniforms issued after 1687. The number of

buttons on the pocket flaps should however be three for privates and the

shoulder straps are incorrect. Only the cavalry

appeared to have had shoulder straps in the Great northern War and then

only on one shoulder.

Buttons on the backside near the waist were also present

during this time period.

-

M/1756 which probably was not particularly

different from the earlier uniform.

-

M/1765 which was inspired by Prussia's uniforms

-

The Gustavian

uniform which was designed

by Gustav III himself in

1779.

|